Don't Let Loss or Fear Steal Your Compassion

We need it now more than ever

Come, loves, let's stand here

after madness. The world

is not over, only broken.

There are old books, there are horses

in the lemon trees. There are children, still,

waiting in the classrooms, looking up

with tired eyes full of wonder.

Look at them. There is work we have to do.

~Joseph Fasano

On the morning after the election, my teenage son woke up expecting, as most of us did, that we would not know the results yet. When I told him what had actually happened, I could see fear well up in his eyes. He is old enough that we had talked about the policies at play in this election and their roots within the history of elevating a lust for power over knowledge, values, community, and rights—including the rights of people he knows and cares about. Though no parent wants to see fear in their child’s eyes, I don’t regret his grasp on the reality at hand.

There are concerning trends surfacing among white boys and young men in the wake of the election that indicate a renewed draw toward the allure of power and privilege at the expense of other people’s rights and wellbeing, even, it seems, the rights and wellbeing of boys’ own friends and loved ones. I don’t delude myself into thinking that my son’s awareness of the stakes of this election will make him immune to these trends, which seem largely untethered from the values of boys’ parents and communities. But, as a teacher, I do believe that providing children with information, knowledge, and exposure to histories and stories that expand their view beyond their own experience and self-interest is the best hope we have for fostering compassion and a commitment to mutual responsibility in the next generation. I hold this as one of my most serious responsibilities at work and at home.

It is painful to see sadness and fear in our children’s eyes, as they discover some of the crueler truths of the world. But if we are going to move toward a brighter future, we will need to work on behalf of our children, while also preparing them to take hold of their own future with clear eyes. My deepest desire for my son is that he learns to cultivate and sustain his own capacity for a form of hope that is rooted in balancing knowledge and understanding—even when that understanding is difficult to bear—with an awareness of the good that does exist and a belief in the possibility that it is within our power to shape a less broken, less cruel, less frightening world.

The novelist, Michael Chabon, once wrote:

“Everyone, sooner or later, gets a thorough schooling in brokenness. The question becomes: What to do with the pieces? Some people hunker down atop the local pile of ruins and make do, Bedouin tending their goats in the shade of shattered giants. Others set about breaking what remains of the world into bits ever smaller and more jagged, kicking through the rubble like kids running through piles of leaves. And some people, passing among the scattered pieces of that great overturned jigsaw puzzle, start to pick up a piece here, a piece there, with a vague yet irresistible notion that perhaps something might be done about putting the thing back together again.”

I’m certainly not suggesting that our primary role as parents or teachers should be to school our children in the brokenness of the world or to fill their hearts with fear. Children need to experience the beauty, joy, and love that life has to offer in order to develop any sense of investment in working toward a world that is more beautiful, more joyful, and more full of love. But children also need us to acknowledge honestly the places where the world does not yet fulfill these promises, so that they can feel we are by their side as they brush against the broken edges, knowing that they are not alone, and so that they can look to us as models for what to do with the jagged shards. As the poet, Andrea Gibson, recently said,

“Why, when we hate the world, don’t we scream, I hate it? Because I love it, and I know what it could be. We know what it could be because it is already so—in moments, in places…

It’s not just my calling, it’s everyone’s calling, to find beauty where we are told it can’t be found, and to make it where it isn’t yet.”

When I saw fear and sadness fill my son’s eyes on the morning of the 6th, my own felt magnified and it was hard to get words out. I think the amplification of our own fears, which swell viscerally when we see them reflected in our children, is the primary reason we often try to silver-line difficult truths for them. We are protecting our own adult hearts. But my message to him was simple, and it echoed a message I’ve tried to offer him his entire life. I said that making the world better is hard, and that sometimes, despite our best efforts, things go wrong. But that doesn’t mean we’ll stop trying. I said that, even though it feels sad and scary right now, history is full of examples of progress happening after terrible setbacks. This is a moment in time, not the end. And I said that our job now is to do our best to keep working for a better world and to look out for those who are vulnerable and do what we can to protect and care for them. We take in the heartbreak, but we keep caring, and we keep working from our care, not against it.

I said this through my own tears, and I don’t regret that either, because I want him to know that we can feel the world deeply and even painfully at times, and still love it and recommit to loving it. I want him to know that we don’t have to become harder or tougher or more numb in order to be brave. I want him to know all of these things, and I want to make sure that I remember them myself, as well.

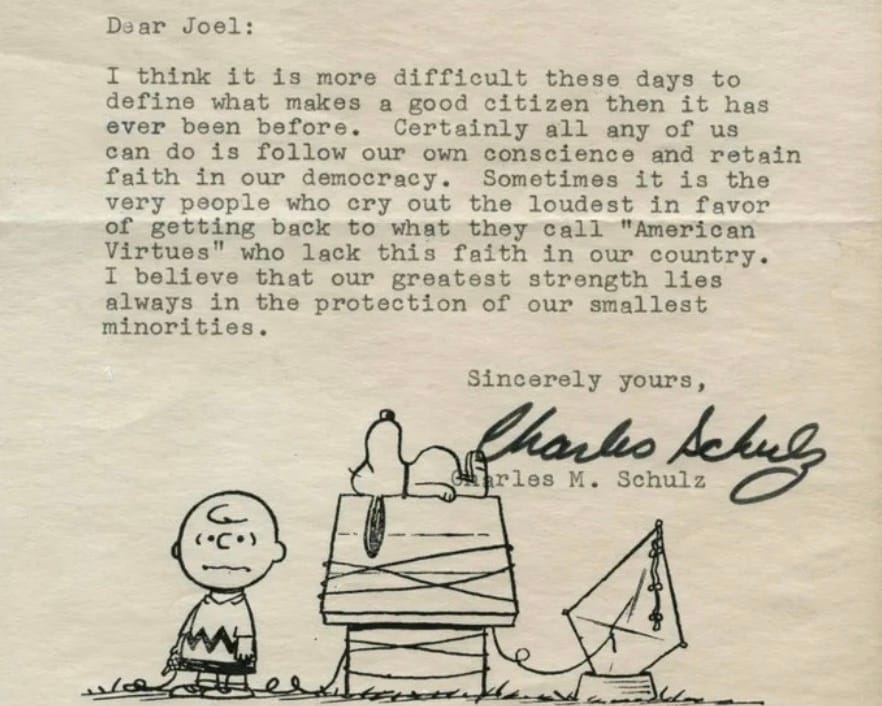

In 1970, a ten-year-old boy named Joel wrote to Charles Schulz to ask what makes a good citizen. The letter was part of a school assignment, and the photo above is of Schulz’s response. He said,

“I think it is more difficult these days to define what makes a good citizen than it has ever been before. Certainly all any of us can do is follow our own conscience and retain faith in our democracy. Sometimes it is the very people who cry out the loudest in favor of getting back to what they call ‘American Virtues’ who lack this faith in our country. I believe that our greatest strength lies always in the protection of our smallest minorities.”

I’ve been thinking about Schulz’s advice this week, as I’ve continued to consider both how we guide our children through this difficult moment and how we navigate it ourselves. There has been much talk of the notion that we’ve landed in our current reality as a result of, essentially, an overreach of compassion—that too much focus was given to the rights and protections of our “smallest minorities,” to use Schulz’s words, and that this alienated swaths of voters. Whether it’s labeled as “anti-woke” or “identity politics,” make no mistake about what these critiques are asking of us. The underlying message here is not about whether we’ve been overly particular with terminology or pronouns. The message is, “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.”

Accepting this stance requires an abandonment of compassion under the guise of electoral strategy. History tells us where that path leads, and it is not toward protecting democracy; it is toward brutality. As Holocaust survivor, Irene Weiss, explains, we must be wary of accepting permission to marginalize any group of people under the false premise of a greater good. She cautions against, “even a hint of permission that it’s okay to attack this group or exclude this group or shame that group.”

There is also good reason to take issue with the strategic argument in and of itself, as it does not align well with the facts of the moment. But, most importantly, accepting this premise signals a resignation to a deeply repressive future, one that autocracy expert, Balint Magyar, describes as, “morally unconstrained collective egoism.” We cannot afford to concede the very values that serve as the bulwark against this dark path.

Leading with compassion, instead of running away from it, does not place values above results, as we are often led to believe. It places values at the center of results, which research suggests can be extremely effective, if we leverage and communicate our values well. When we instead capitulate to the cynicism of abandoning our support for one another and give into a more isolating, individualistic stance in the name of winning, we only succeed at entrenching the narrative that compassion is inherently weak and uncompelling. In doing so, we participate in making this a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is a stance I’m unwilling to give into and one I certainly don’t want to transmit to my son. As Roxane Gay wrote this week,

“We cannot abandon the most vulnerable communities to assuage the most powerful. Even if we did, it would never be enough…We act as if they get to dictate the terms of political engagement on a foundation of fevered mendacity. We must refuse to participate in a mass delusion.”

Instead, when we begin with a message of seeking commonality in our humanity and in a shared value of standing up for one another, we inspire people to do just that—to stand up for one another. We’ve seen this happen again and again across history. These movements, not cynicism, are the only forces that have ever defeated cruelty and marked true progress. Anat Shenker-Osario has conducted extensive research both in the U.S. and in repressive political regimes around the globe. Her work has demonstrated that ceding shared values is not only an ethically dubious position, but also a deeply ineffective strategy. She reminds us, backed by her research on real victories over repressive regimes around the world, that, “It is actually in the bleakest of times that you need to present the brightest dream.”

This is not a moment to give up on compassion, to give up on advocating for the least powerful among us, or to give up on nurturing these values in our children. This is a moment, instead, to remember what Charles Schulz advised a little boy decades ago, that “our greatest strength lies in the protection of our smallest minorities.” Compassion only becomes a weakness when we allow ourselves to be convinced that it is one and act accordingly.

Despair nudges us to concede our future to the darkest interpretation of the current moment. But strength does not lie in abandoning people or communities. Instead, let’s commit, “to find beauty where we are told it can’t be found, and to make it where it isn’t yet.”

Wishing you the courage to keep caring and to act on your care,

Alicia

If you think someone else in your life might need some hope, please share. It’s always easier to hold onto hope when we’re not doing it alone.