Everything Precious Is Fragile

It’s okay for children to know that

“But there will be certain things—

the quiet flush of waves,

ripe scent of fish,

smooth ripple of the wind’s second name—

that prefer to be written about

in pencil.”

~Naomi Shihab Nye

In the time between my son’s first birthday and his fourth, we navigated a pretty wild and unexpected array of losses together. Some losses were quiet and ordinary, the kind you can anticipate, but which are still always more deeply felt than any knowing can prepare you for. Others were more dramatic, knock-you-sideways kinds of losses. I’m an early childhood teacher with many of years spent supporting children's growth and advising parents on how to explain the more difficult moments in life to them. I believe—and all my experience and plenty of research tells me—that it is important to be honest with children, even when it’s hard. But, man, is it hard sometimes.

As the losses piled up, I wanted more and more to protect him from any additional hurt, disappointment, sadness, uncertainty, or fear. I worried about whatever the next looming thing might be. Even fairly normal bumps in the road, like the weekend our dog mysteriously stopped eating, made my chest tighten in anticipation of having to break the news of more grief to him. (That dog is sleeping next to me now, by the way, a content senior citizen. We dodged that particular sorrow.) My heart broke with his little heart each time, and I worried about how many things could go south before it became part of his disposition to assume that everything always would.

Mostly, I managed to follow my own teacherly advice, telling him the truth as simply as I could in the small doses that allow a young child to turn tricky facts over in their mind and ask questions if they need to. I wasn’t perfect. There were times when the circumstances prevented me from giving him all the facts, and there were times when I truly believed he didn’t need to know every detail at the age of two, or three, or four. But most of the time back then, and in the years since, I’ve tried to remember that the trustworthiness of our loved ones keeps us steady, and it has been essential for me to be that bolster of reliability. I’ve also tried to remember that life is full of fragility, that the most precious parts of life are usually precious precisely because they are not guaranteed indefinitely; learning this is hard and recursive, but learning it in the company of someone who cares about you is better than learning it alone.

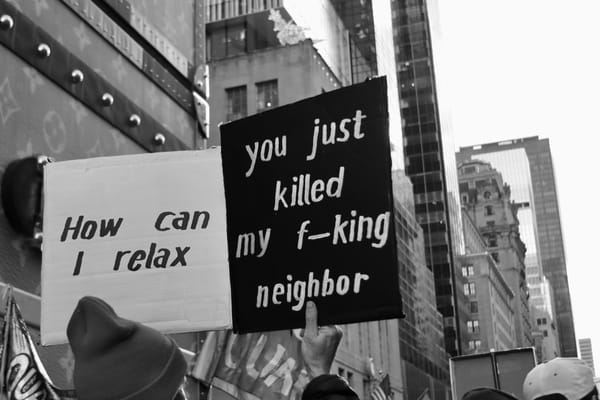

In recent weeks, an ad for a new AI app that promises to keep your loved ones in your life forever has been circulating and provoking understandably extreme reactions. Some reviews have called it “evil,” “dystopian,” “demonic,” "a real-life Black Mirror." I understand this reaction, but I also think the language cuts short important conversations about the deeper set of needs, which make this kind of innovation so likely to proliferate. Grief can be crippling, and humans have been trying to avoid and circumvent loss since Orpheus descended into the Underworld in search of Eurydice. It is embedded in human nature to look for ways to pull ourselves back from pain. In the U.S., it surely doesn’t help that bereavement leave is often not an option, mental health professionals are stretched thin, and their services are often not covered by insurance—if you have insurance. The temptation to avoid or numb loss is primal and our support networks are fragile, frayed, and insufficient at best.

So, of course this is how we would try to use a new, eerily lifelike technology. And this app isn’t the only one. “Grief-tech” is a growing niche within the AI industry (though the creator of this particular app says that the intention is not for it to serve as grief-tech, but rather as a way to assert ownership over your AI persona). I am in no way making an argument in favor of using these tools. But I do think it’s more helpful to begin from a place of compassion for the deep, human desire that can make technology like this compelling, and to recognize the fact that the development and adoption of these tools reveals severe cracks in our care systems and in our cultural tolerance for making sense of loss.

Feeling desperate for connection or desperate to alleviate pain leads people down treacherous paths, as does the more mundane desire to simply soften the edges of any possible discomfort. As we’ve seen in the recent stories of several teenagers goaded to suicide by AI companions, and as research from groups like Common Sense Media reinforces, turning to artificial care can be a dire or even a deadly choice. The descent of Orpheus and his ultimate torment doesn’t seem too hyperbolic of a metaphor, given these stories. But this choice is also one made within the context of a social fabric that frequently leaves more human and humane support out of reach, and a culture that constantly prods us to circumvent discomfort and complexity. We go to great lengths to cheat time, grief, and the unavoidably fraught rhythms of the lifecycle every day.

There’s also something specific about the ad for this particular app that doesn’t just tap into our natural uneasiness with our own grief. The entire narrative of the ad stems from the idea that our children could have a relationship with relatives they otherwise would not have been able to know. The ad begins with a pregnant mother talking to an AI version of her own mother and then proceeds, frame by frame, to take us through her son’s childhood, as he talks with his deceased grandmother at several points in time, as if they were on a virtual call. The ad ends with an emotional conversation between the boy, now an adult, and the facsimile of his grandmother, as he shares the news of his own soon-to-be-born child, before cutting briefly back to his own mom, years earlier, setting up the app. It isn’t exactly the mother’s own grief the technology is abating in this particular marketing story, but the anticipatory parental longing for a generational relationship that will never exist in reality.

Again, I’m sympathetic to the desire. My own mother died when I was a child. She’ll never know my son or me as a mother, and he will only know her through photographs and family stories. Additionally, several of the losses we experienced during those difficult first few years of his life will only be hazy recollections for him—the kind of memories that blur over time into the stories we’re told. Of course, there is sadness in this. But there is also a lot of beauty and meaning in the experience of passing narratives and love across generations, while being honest about the losses these stories encompass. And it’s the beauty and meaning that I think we need to remind ourselves of when we're tempted to paint new, holographic realities in order to avoid loss.

The stories we tell so we can hold and share memories are important. They are one of the strange gifts of loss. We learn to shape our memories into personal anecdotes, family tales, and inherited lullabies. We create intimate oral histories and pass down recipes and photo albums. And, out of all of this, we establish rich timelines and tapestries for ourselves and for our children. These archives are not the same as conversations or flesh-and-blood contact, but they also do something unique that the relationships themselves couldn’t even do—they situate us in time and in shared meaning as we say, not only, “this is who this person was,” but also, “this is who they were to me, and this is why that mattered.” And, as we recall and share our histories, we come to know ourselves better, and those we convey our memories to also come to know us better.

Knowing we will one day have to do this, and that others will do it for us—that they will hold our memories within their own stories, make sense of who we were to them, and share us with others as a thread within the individual they've become—is part of what makes our relationships and connections so precious in the first place. This is not to suggest that our relationships are only significant because they are impermanent. But, surely, if eternity were guaranteed, no moment would be as worthy of savoring, and we would not come to know ourselves or one another as well.

This isn’t only true in death, but at each point along the path of our individual lives, as we change and as those we love change. I miss the chubby cheeks and sticky hands of my son when he was a toddler. There’s a part of me that would give anything to feel the peace of his heavy head resting on my shoulder again, breathing the soft breaths of baby sleep. But I also know that part of the sweetness of those memories is their brevity. And I know that part of the sweetness, then and now, is in the messy, unpredictable, un-algorithmic nature of getting to know another person deeply over time, not only frozen in a singular moment.

There is also a particular kind of strength that can only be forged through honest reckoning with loss. I don’t think about this as resilience, which implies a bouncing back or a quick return to our previous selves. We don’t come out of loss entirely renewed, because we are inevitably transformed as we manage difficult transitions. And in this transformation, we learn, not only that we can persist through pain, but also that meaningful understandings are often unearthed through change, even when that change might feel unwelcome. Though we’re made stronger by this process, I also think that, when we navigate loss and change with openness and care, we can be softened by it in important ways, too. We have an opportunity in grief to become more compassionate and more able to receive and hold others’ suffering. Naomi Shihab Nye reminds us in another poem,

“Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.”

By creating the perception of an immortal family for a child, we may feel that we are protecting them from pain, or offering the gift of a relationship that they would otherwise never be able to know. But we are also robbing them—of their ability to learn that it’s possible to survive sadness and even to be transformed by it in important ways, of their ability to get to know us better through the experience of sharing stories and family histories told and retold over time, and of their ability to locate themselves within the arc of time as they learn to construct and share their own stories.

Permanence is especially hard for young children to understand. They possess a rich capacity for magical thinking, which often makes it difficult for them to comprehend that anything could be finite or final. This is why, in the classroom, we talk endlessly about the lifecycle of plants and the metamorphosis of butterflies, and we share our collective sadness over the loss of class pets. Children are learning that they exist within time and within change. Their fantasy play is important and valuable, but it also makes them vulnerable to being tricked into living in fabricated realities. We owe it to them to hold our own fears with a sense of responsibility and a commitment to avoid manipulating their reality in order to hide from our own.

Among the first losses in the domino sequence of losses that marked my son’s early years was my grandfather—someone I’d known well for my entire life and whom I wrote a little bit about here. We traveled from New York to Minnesota to visit him very close to the end of his life when my son was just a few months shy of his second birthday. There was a lot of family storytelling on that trip, and my uncle recorded hours of my grandfather recalling his own life, prompting him to retell stories we had all heard many times before. My son has vague memories of that trip, and he remembers my grandfather in fleeting bits and pieces, if not well. But he has the photos we took, as well as many that predate his own life, and he has the stories, both in our continued retelling and in the recordings that were made that week. And, perhaps most importantly, he has the knowledge that it is possible to both let go of someone and to hold onto them through time in our own mind, without needing to create false realities. I suspect that this early experience of loss helped both of us to manage the series of other losses that followed, none of which could be as well anticipated or as carefully and lovingly curated, which is more often the case.

It was all extremely hard. Those years of grief upon grief imprinted differently but profoundly on both of us, I'm sure, as we moved through them together, and as I struggled to decide what information to share each time. I'm certain that neither of us is the same today as we would have been had that period of time been simpler and more gentle on our hearts. In acknowledging the beauty and the important transformations that loss and grief can create, I don’t mean to discount the hardship. It was rough. And I wish that it could have been less so. But, despite that wish, I still would not have wanted to live in an indefinite hologram or to create one for him. We are who we are today, in part, because we charted an honest course through those years, as much as we could manage. We learned to hold sadness, memories, and love together, and to cherish joy wherever it can be found and however fleeting it might be.

“Yet I turn, I turn,

exulting somewhat,

with my will intact to go

wherever I need to go,

and every stone on the road

precious to me.

In my darkest night,

when the moon was covered

and I roamed through wreckage,

a nimbus-clouded voice

directed me:

‘Live in the layers,

not on the litter.’”

Wishing you care and the gift of memories held honestly and lovingly,

Alicia

P.S. All of this week's Helpful & Hopeful links below dig more deeply into the ideas explored in this note, and are invaluable resources to bookmark for when you may be navigating your own losses and memories.

A few things I've found helpful and hopeful…

- Andrea Gibson's newsletter, Things That Don't Suck, which continues posthumously through the writing of their wife, Megan Falley, is an incredible archive of moving through grief with an open, honest heart. I also highly recommend the beautiful documentary about their life and death, Come See Me in the Good Light.

- Chloe Hope's newsletter, Death and Birds, beautifully merges her work with birds and as an end-of-life doula to consider fragility and preciousness.

- One of my graduate school (and beyond) mentors, Jonathan Silin, has been writing about these topics for decades. His work has shaped my own thinking significantly, particularly as it relates to our conversations with children. You should read his books.

- Benjamin Riley is writing thoughtfully about the relationship between AI, education, and what it means to be human. I've found his work especially helpful.

- And finally, about that dog I mentioned earlier, I recommend dogs. They soothe a million wounds.