Fighting for Every Child

Because we can’t settle for 1 out of 3,800

“Give them peppermint to put in their pockets as they go

to school. Give them the fields and the woods and the

possibility of the world salvaged from the lords of profit.

Stand them in the stream, head them upstream, rejoice

as they learn to love this green space they live in, its

sticks and leaves and then the silent, beautiful blossoms.”

~Mary Oliver

Several weeks ago I shared a video, at the end of this note, of children at Liam Conejo Ramos’ school reading letters they had written to ICE—letters asking for recognition and kindness in the face of brutality—and speaking about their hopes for Liam’s safe return to their community. Since then Liam and his father have been returned home to Minnesota, surely at least in part as a result of the collective rage that the photos and video of their abduction prompted. The massive outpouring of response to Liam’s detention pushed political leaders to visit the Dilley Detention Center in Texas, where he and his father were being held, and to fight for their urgent release. The fact that Liam and his father are home now is, without question, extremely good news. We should celebrate the safety and freedom of every single child, because no child should ever be seen as a mere data point. Every child saved from pain and trauma matters.

It’s also necessary to celebrate these glimmers of good news, because it is otherwise so easy to be pulled down tunnels of despair by the constant stream of frightening, dispiriting information that so often dominates our screens. Pausing to celebrate whenever our effort to keep each other safe proves effective is necessary to maintain the stamina required to keep going, especially at a time when the need for this kind of effort often seems herculean and unrelenting. As the Minnesota organizer, Ashley Fairbanks, reminds us,

“We need to take a moment to celebrate when a good thing happens. It is fuel for the work. Feel the joy. Take a big breath in. Let yourself cry.”

But we also have to remind ourselves to do just that—to use these moments as fuel, not as permission to tie a single task up in a neat and reassuring bow. It is crucial to both take a moment to feel the upwelling of possibility and tangible hope that is provoked by good news hard won and to remind ourselves to keep going, especially in a landscape where no child’s story of fear is singular. There are so many more children who also need our voice.

Galvanizing individual narratives like Liam’s are important. Without them, too often, it becomes easy to ignore suffering or to feel that the scale of suffering is too big to solve. As humans, we do have a remarkable capacity to empathize with those who are far removed from our own daily lives, or whose lives seem radically different from our own. But this is not our default. It is usually much easier for us to empathize with individuals whose image or narrative offers some clear link to our own lives. Our brains become overwhelmed by suffering too far removed, especially when that suffering is happening at a large scale.

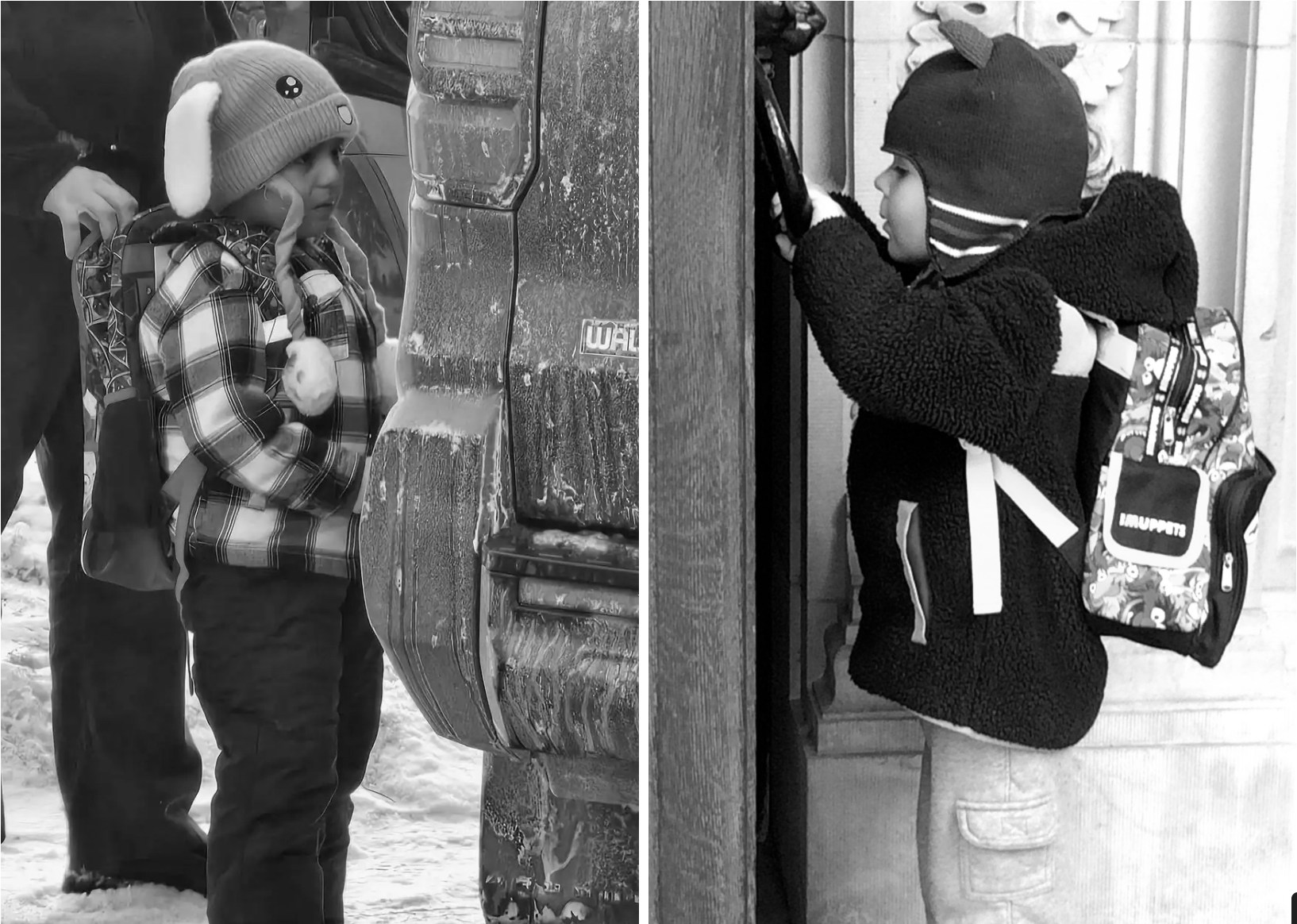

This is why the story of Liam and his father went viral; their image was familiar and singular enough for us to hold. The combination of the fact that their abduction was caught on camera, that the use of Liam as bait to try to lure the rest of his family out of their home seemed especially cruel, and, most importantly, that little Liam in his bunny hat and Spider-Man backpack looked so much like our own children, children we know, or our recollections of ourselves at his age—all this stirred our hearts and compelled our voices. His image drew so many people in, because he felt immediately like a representative of every child we know and love.

It is important to act on these moments of common recognition. Individual stories like Liam’s are often the ones that turn the tide. They break through the fog of our inundating news feeds and personalize circumstances that otherwise feel too big to wrap our minds and hearts around. And they create a necessary focus that drives us to act, instead of continuing to passively consume information, feeling helpless. Images like Liam’s push us to step over that feeling of helplessness and to realize that we do, indeed, have power, particularly when we use our voices together.

Individual stories trigger an overlapping neurological response, as we literally feel the experiences of others activated within our own, biological survival systems. Powerful stories of others prompt us to act as if they were our own stories, because our brains and our bodies literally feel as though they are. Individual stories also make unmanageable problems feel, temporarily, manageable. We must get this child home feels possible where bringing thousands of children home feels insurmountable. This is important and valuable, as long as the single story that activates us represents a starting point and not the totality of our response.

But the ease with which we connect to individual stories also sets the stage for an emotional catch-22 that we must vigilantly attend to and guard against. Frequently, when the single story that initially broke our hearts and pushed us to act seems to reach a resolution, we exhale and step back and allow ourselves to feel just as comforted by the apparent conclusion of that story as we were previously inflamed by it. It is natural to long for happy endings and emotional closure. It’s surely easier to give into these feelings than to contemplate the many stories behind the one that compelled our action, even though these other stories—stories that would likely feel just as personal and significant if only the right photo or video had hit the media at the right moment—remain unresolved. Truthfully, even the single story that we felt so connected to is rarely as neatly concluded as we wish for it to be.

It felt good to see images of Liam playing with the pilot on his plane home from Texas and smiling at us from his own living room, after seeing him languish in his father’s arms in detention. It felt so good to see Liam safe that many people even wanted to believe he might have made an appearance in Bad Bunny’s super bowl performance. Images of resolution make us feel that our fight matters. Massive numbers of people, politicians, and media outlets spoke up for this little boy and he came home. We should feel vindicated by the evidence this provides for our potential to make a meaningful difference, even against overwhelmingly powerful forces. We should celebrate every child’s safety and every moment when our empathy and our moral outrage successfully makes a difference, as it did for Liam. But it’s also important that we not allow these moments of victory to cloud our ability to see the larger picture, for other children or even for this one child.

The larger picture for Liam is that he was not at the super bowl—of course he wasn’t—because his family is still facing significant risk and because he is still grappling with the emotional repercussions of a harrowing trauma. It’s important and valid for us to feel good about his safety, but we should pause when our tendency to seek a happy ending allows us to become dissociated from reality. Imagining and hoping for a traumatized five-year-old to take the stage in front of millions of people is an example of the type of moment that we need to learn to mentally flag as a signal that our natural, human desire for a comforting conclusion to a single story has escaped the bounds of reality and removed us from the work that remains to be done for him and others.

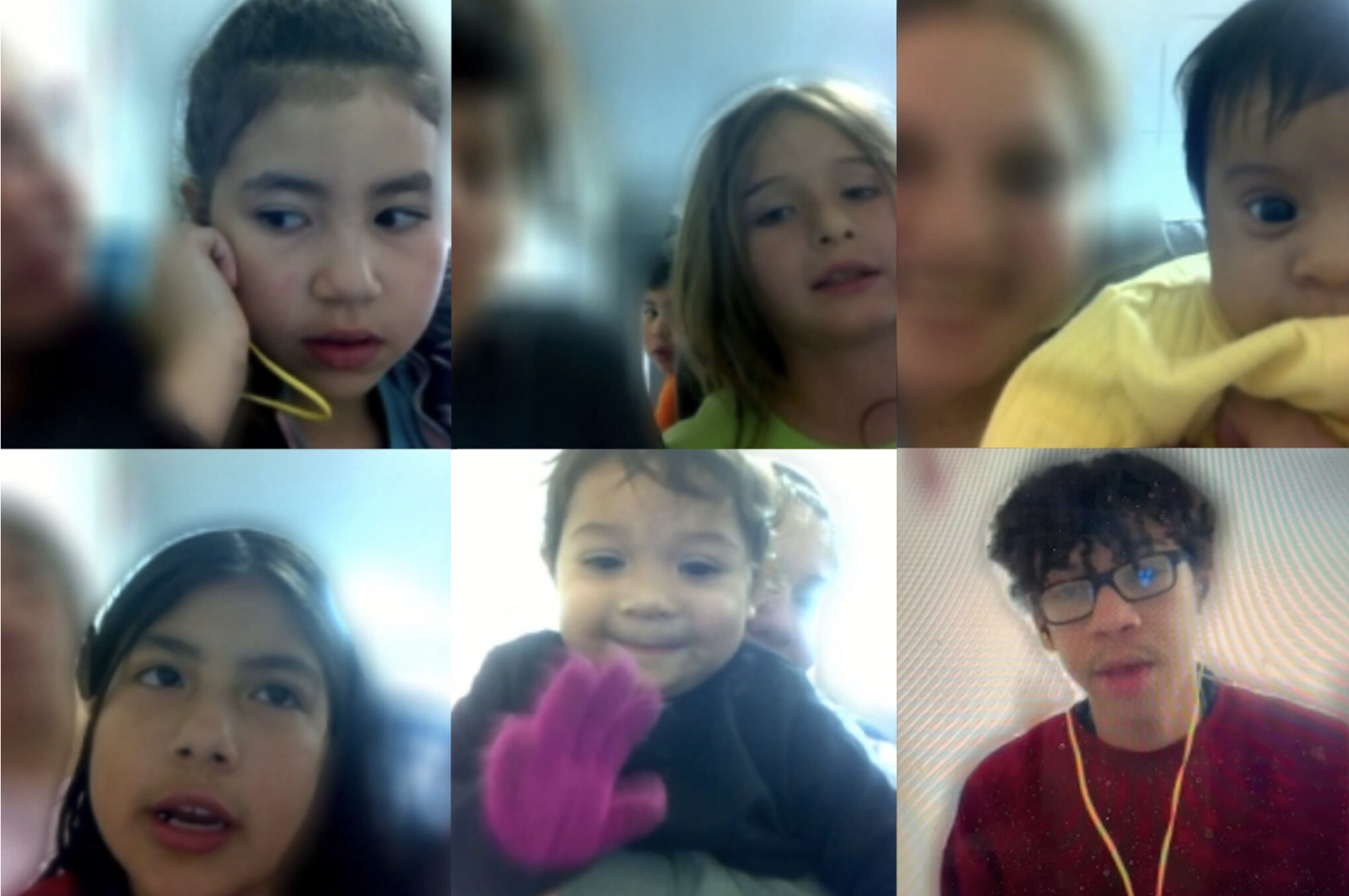

Widening the lens beyond Liam himself, 3,800 children, including infants, are still locked away, many in the same place Liam was sent to, which immigration lawyers have long described as “baby jail.” It is important to celebrate wins. And it is also important not to allow that celebration to satisfy our desire for emotional resolution so thoroughly that the comfort of a single point in a much larger picture obscures our view of the rest of the picture.

There are many children like Liam who still need our outrage and our voices. They are each just as precious and important as he is. Each and every one of them would have a long road to recovery, even if we managed to bring them all home tomorrow. But bringing them home is still their best chance at the healthy future they deserve. And the longer they stay the longer it will take for them to heal. Instead of scrawling a reassuring happily-ever-after note on the photos of Liam safely at home, we need to find ways to inscribe the emotions that his sweet image provoked onto the thousands of other children like him, so we keep fighting for them, too. The single story must become a symbol for the larger story, igniting our continued fight, not an illusion that there was really only ever one story.

If it feels unsustainable to keep attending to these very difficult realities, I get it. It’s hard not to feel despair in the face of the true scale of children’s suffering. This is why it’s natural to want to focus on a single case that feels possible to address and resolve.

But I would offer two reminders in response to the temptation to turn away and tune out. First, what these children are enduring is far worse and far more intractable than the demand placed on our conscience by refusing to look away from them. I don’t say this to create a sense of shame but simply because it is a fact. And, second, the best antidote to the feeling of overwhelm that can easily make us want to tune out from unyielding, upsetting information is to do something proactive to make a difference. I’m planning to write more about the research that supports this, and the way we see it manifest in children, in a subsequent note. But, for now, I will just offer a reminder that despair and exhaustion are more often the result of the inertia of our inaction than of the news itself.

"Everything from research to history to art will tell you it is the exact opposite: that sometimes we aren't exhausted because we are aware of too much, we are exhausted because we are doing too little…People who feel agentic aren't as tired. They are not as easily overwhelmed…The more time you spend doing something, whatever is possible for you to do in your space in the world, the less exhausted you are by the onslaught of information that really wins when it can convince you that the only thing you can do is watch what is happening."

With this in mind, instead of sharing my usual round up of links covering a range of topics after the note, I’m going to share two sets of links here—several that will help you understand the broader picture that Liam’s story fits into, and then some ideas for ways to become more active on behalf of these children and in limiting the likelihood of the number of detained children continuing to grow. Because hope resides in action.

Putting Liam's Story in Context

- The Children of Dilley

- "I have been here too long": Letters from the Children Detained at Dilley

- "Even in Russia, they don't treat children like this"

- Even if ICE left tomorrow, the damage to kids is already done

- Daily Number of Kids in ICE Detention Jumps 6x

- Plans for an expanding network of detention centers

Ways to Begin Taking Action

- Find local organizations to learn from and engage with. This collection of resources in key target states is a good place to start.

- If you're in NYC find a Hands Off event and sign up for updates.

- Distribute whistle kits in your community. Or join the network of 3D printers if you have the technical capability! Or donate supplies to whistle printers.

- Call your representatives. I know it feels tedious but cummulatively it does make a difference.

- Find out how to prevent more detention centers from opening in your community.

Wishing you the endurance to keep paying attention and the resolve to continue working toward a better world,

Alicia