Firefighters Go In Scared

Lessons in courage from a preschool classroom

Letter to a Bridge Made of Rope—

To the shepherd herding his flock

through the gorge below, it must appear as if I walk

on the sky. I feel that too: so little between me

and The Fall. But this is how faith works its craft.

One foot set in front of the other, while the wind

rattles the cage of the living and the rocks down there

cheer every wobble, your threads keep

this braided business almost intact saying: Don’t worry.

I’ve been here a long time. You’ll make it across.

~Matthew Olzmann

The winter that I was pregnant with my son was one of the snowiest on record for New York with over 60 inches of snow falling in the city by the end of February. As I made my way carefully down the steep, snow covered steps of our brownstone apartment building, where the railing would often be coated in ice by the morning, and through the slick, white washed streets of Brooklyn to my classroom, I remember feeling acutely aware of the fact that I was now responsible for two people’s safety.

We often view the risk taking tendencies of children and teens and the increasing caution that emerges with age as an inevitable feature of development. There is some truth to this. The prefrontal cortex, which plays a significant role in judgement and decision making, takes decades to reach maturity, though the full developmental story of risk taking is complex.

But, as I stepped gingerly over snow drifts and vigilantly watched for ice patches that winter, I also remember thinking that surely we become more cautious, at least in part, because the spheres of our love and responsibility widen. The directionality of our relationships becomes more complex and varied, as we are no longer solely dependent on those with greater maturity. We build bridges of mutual care and obligation, as we move into adulthood and cultivate lives that are intertwined with people who are dependent on us and on whom we simultaneously depend. As our love becomes more complicated and mature, our responsibility for those we love grows and our safety feels less and less our own.

The irony of the fact that this caution grows out of love, and out of our evolving understanding of the impact our lives have on others, is that it can make it harder to show care for those beyond our most intimate circle, if that care involves any risk, real or anticipated. Putting ourselves at risk begins to feel like a risk to those we care for as well, and this is harder to tolerate and grapple with than anything we may have previously perceived to be purely individual.

And yet, I believe that it is also possible for love to stabilize us and undergird our courage if we know how to channel it. This is something that I think we can learn from both the youngest children and the bravest adults.

As fires have raged in LA over the past several weeks, defying containment and putting many people’s lives and homes in direct and immediate peril, and as the upcoming presidential transition has created a strong sense of ominous fear for many others, I’ve been thinking about bravery in general and about firefighters in particular.

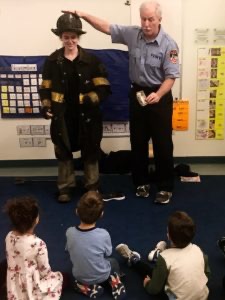

Throughout my years working in preschools, I’ve hosted firefighters in classrooms many times. One might assume that this is because young children often idolize firefighters, making them sought after celebrity guests. But there is also a more pragmatic reason. Despite the fact that many young children adore firefighters in the abstract, in the midst of a real emergency, when firefighters are fully decked out in their gear, including a face mask and a noisy breathing apparatus, children often hide from them, which can put a child’s life at greater risk. So we bring firefighters into the classroom to help children build familiarity with the emergency equipment and to humanize the firefighters, who might one day be searching through smoke, behind a dark mask, to save them.

Of all these visits over the years, there is one that is rooted in my mind more firmly than any other. Lt. Ray Brown was unique among the firefighters I’ve met in classrooms for two reasons. First, he was the father of one of the teachers in the class. This made him real to the children in a way that does not always happen. Firefighters occupy an almost superhero-like space in children’s imaginations. This idolization separates them from reality. But Lt. Brown was a dad. And not just any dad, he was their teacher’s dad. Children are usually excited during these visits but there is also often a tension that arises out of a mix of awe for some and nervousness for others, keeping them slightly distanced from the hero at the front of the room. But the fact that this firefighter was their teacher’s dad, combined with his warm, gentle nature, created a relational bridge that allowed the children to be fully at ease in his presence.

The second thing that made Lt. Brown’s visit unique was his helmet. He showed it to the children and explained why it’s important for firefighters to keep their heads protected during a fire. Then he turned it over and showed them the inside. Tucked within the headpiece was a photo, which he pulled out so the children could see it more closely. It was a photo of their teacher. He then explained that, just as the children keep photos of their families inside their cubbies at school to help them feel brave when they are lonely or missing home, he has always kept a photo of his daughter inside his helmet to help him feel brave.

This is a common practice among firefighters, and while the photos are surely a reminder to do everything possible to make it home safely, I’ve also heard firefighters explain that the photos remind them that they have other families’ loved ones in their hands. Their own palpable human vulnerability—their love for their families—reminds them that the people they rescue are also loved in this deep way. That connection creates a sense of purpose strong enough to bolster their courage as they walk into flames.

This was a powerful message for young children. Children are inherently vulnerable and are often scared. It goes with the territory of childhood. They find temporary courage in imagining themselves as heroic figures like firefighters and superheroes through their play. But it is the bond with a secure caregiver that always provides the deepest sense of safety and establishes a lasting well of confidence and resilience. And they find comfort and reassurance throughout the school day by reminding themselves of the people who love them most. Knowing that this was true for their heroes as well was revelatory. As it turns out, we are all only as strong as we are vulnerable.

It is hard for me to imagine a more significant message for adults either. I think this is the reason I only have one low resolution photo of Lt. Brown showing the picture of his daughter to the class. All of the adults felt just as connected to him in that moment as the children did.

We are all just a heartbeat away from the vulnerability of childhood and the need to feel connected to the people who love us. We are all afraid. Being brave is not about being impervious to fear. Being brave is about being so aware of how vulnerable our love makes us that we are willing to put ourselves at risk to protect someone else’s love.

Many people are afraid right now, and when we are afraid it is easy to turn inward and to focus on protecting ourselves and our own intimate circles, even if that means turning our backs on others. It is tempting, instinctive even, to hide. But when we hide, just like the child in the burning building, we don’t become safer, only more isolated.

However, as Lt. Brown’s visit showed us, we can also choose to use our love as fuel for our courage, instead of as justification for our caution. We can allow it to remind us that we are connected by our shared vulnerability, and we can use this knowledge to drive us to protect others.

Though he didn’t share this with the children, Lt. Brown had seen the worst we can do to one another and confronted dangers few of us could imagine. He was among the first of the first responders at the World Trade Center on 9-11, arriving before the north tower collapsed. He and his company were blown across West Street as the first tower came down. As they attempted to rescue fellow firefighters from the debris, the second tower collapsed and Lt. Brown was struck in the head. He was lifted out of the rubble by two firefighters from another company. New York Daily News photographer Todd Maisel captured his rescue and later described the moment, in an essay recalling the day, saying,

“A firefighter was struck by something that fell from the building, his head and chest bloodied. Fellow firefighters were dragging him away from the danger, one screaming ‘hold on, brother, hold on.’”

Lt. Brown’s company survived, and after months of recovery, he returned to work undeterred. He has said, “After September 11, I learned how much pain the human heart can take and how much love it can’t absorb,”

Most of us would not be able to manage this level of courage. It takes an uncommon spirit to rush into flames again and again.

But the truth is, most of us don’t have to master such heights of bravery. Most of us just need to be a little braver than we are, and then a little braver than that. And it’s easier to do this when we remind ourselves to see our own loved ones in the faces of others, whose lives are surely just as sacred to someone somewhere.

Andrea Pitzer has outlined examples from recent history of ordinary people—often with far fewer resources and substantially less freedom than most of us have in the United States today—who nonetheless found paths to courage and action that made a meaningful difference. She notes,

“No one is asking you to break into an FBI office to reveal malfeasance or risk twenty lashes to teach future generations to read. Much smaller, safer actions can still have an effect. It’s up to you what you do, but you can do something.”

I don’t share the story of Lt. Brown here because I expect that it will somehow inoculate us all against fear and motivate us to risk life and limb. I share his story because of his central reminder that we are all afraid, but it is possible to hold our fear at bay enough to quiet the voice that so easily paralyzes us from doing anything at all. We can all do something.

We may not have it within us to run into a burning building. But most of us do have the capacity to care about those who are not our own. This has been on display in Los Angeles over the past two weeks, as neighbors have protected each other’s homes, rallied resources, taken one another in, and spread information about those communities that are most vulnerable, in an effort to direct resources where they are most needed. Yes, there has also been price gouging and extreme rent increases, as some have taken advantage of others’ desperation. But the greed and callousness of some does not erase the fact that every gesture of good will and generosity matters.

Mr. Roger's mother famously told him, in frightening moments, “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” I think this practice not only reminds us that there are people who care and who work to keep us safe, but also that this remains true even when it may feel like malice is all around us. I think it is also a call to our own courage, to observe care and in turn to become helpers ourselves—to see that it’s possible. When we are afraid or when we are angry at the cruelty of the world, we can find strength in noticing and offering care.

As the poet Elizabeth Alexander reminded an audience gathered in Washington Square Park in November of 2016, between poem readings, “We just have to really really dust ourselves off and do our work. That’s all there is to it. Love each other. Do your work. That’s all there is to it.”

Fear is contagious. But love and courage are contagious, too. And everything we do that offers assistance, shelter, solace, or safety to someone else matters.

We can all do something. What will it be today?

Wishing you love and courage,

Alicia

A few ideas to get you started…

Sometimes children are the bravest, and all we have to do is buy cookies.

Teens know what teens need. Help them help each other.

And, speaking of firefighters, there has been a lot of misinformation circulating about the incarcerated firefighters in LA. Listen to this beautiful episode of Vibe Check for a more nuanced understanding.

If you think someone else in your life might need some hope, please share. It’s always easier to hold onto hope when we’re not doing it alone.