Giving Care More Social Clout

How we understand community and resist the appeal of bullies

All we can do in times like these

is offer things that say to others:

You matter to me. The Mason jar

of chicken soup given to a neighbor,

or the clay mug shaped by the hands

of a friend, with a dog and goldfinch

painted on the side—how it arrived

in the mail unbroken. A phone call

out of the blue, or message that says:

Thinking of you. Let’s wrap each other

in gestures so true, no one ever doubts

how much they belong, no one ever

questions whether or not to stay.

~James Crews

In these early fall weeks of unbroken crayons and back-to-school nights, I’m often struck, as a teacher, by the oddness of this cycle of constantly beginning anew. The architecture of so much of our lives for the first many years is shaped by this structure of starting over again and again. There are lots of pedagogical debates to be had over the merits of this structure—the value of summer break vs year-round school, the benefits of grade-level expertise vs looping teachers to follow their students, or the positioning of middle school relative to the grades before and after. But, for today, I’m not interested in these discussions. Instead, as children settle into their classrooms, make new friends, and suss out their social landscape, I’m much more interested in what larger lessons we can draw from this process of coming, again and again, year after year, into community as children do. I’m interested in the lessons children draw from this cycle of constantly building and rebuilding connections. And I’m interested in the lessons we might draw, as adults, from those experiences.

One of the first teachers I worked with always began curriculum night by reminding parents that the most important work of beginning school is not letters or numbers but learning how to come into community—how to transition from being one of only a few at home to being one of many in a classroom, a school, a neighborhood, and on and on over time. Letters and numbers will have their moment. But first, with each new year, children must practice this act of coming into community, finding their place, and reaching out to one another.

As a teacher, I was often focused on the how of this process. So much of the start of the year for teachers is defined by establishing the routines and habits that will shape the social and cognitive environment of the classroom for months to come.

But, as questions about larger social trends toward loneliness and isolation continue to surface, and as we see communities rising up to protect each other from the very demonstrable threats of powerful authorities, I’m also struck by a more basic feature of the recursive experience of constantly entering and renewing community. As children establish community over and over again, year after year, they are not just learning the nuts and bolts of how to form these social webs, they are also developing visceral understandings of what community feels like. And the understandings they construct from these experiences are not uniform. Whether children embed within their hearts and minds the deep sense of security offered by belonging, or the caution and wariness of an outsider, depends on the nature of the communities they enter and the extent to which the overarching ethos they encounter is one of care, welcome, and solidarity or one of power, hierarchy, and precariousness.

The word “community” is often positioned as an unambiguous good. But, as any teacher or child can tell you, the tenor of a community and one’s individual position within its fabric can be extremely delicate. Community can feel like a warm embrace or the giddy buzz of our connections with others clicking into place easily and exuberantly. But community can also feel like the queasy sensation of those connections failing to click, as we find ourselves on the outskirts instead of at the center. At times, community can even feel like the rough shove of rejection or the hot flash of renewed isolation, as we are deemed unfit or unwelcome.

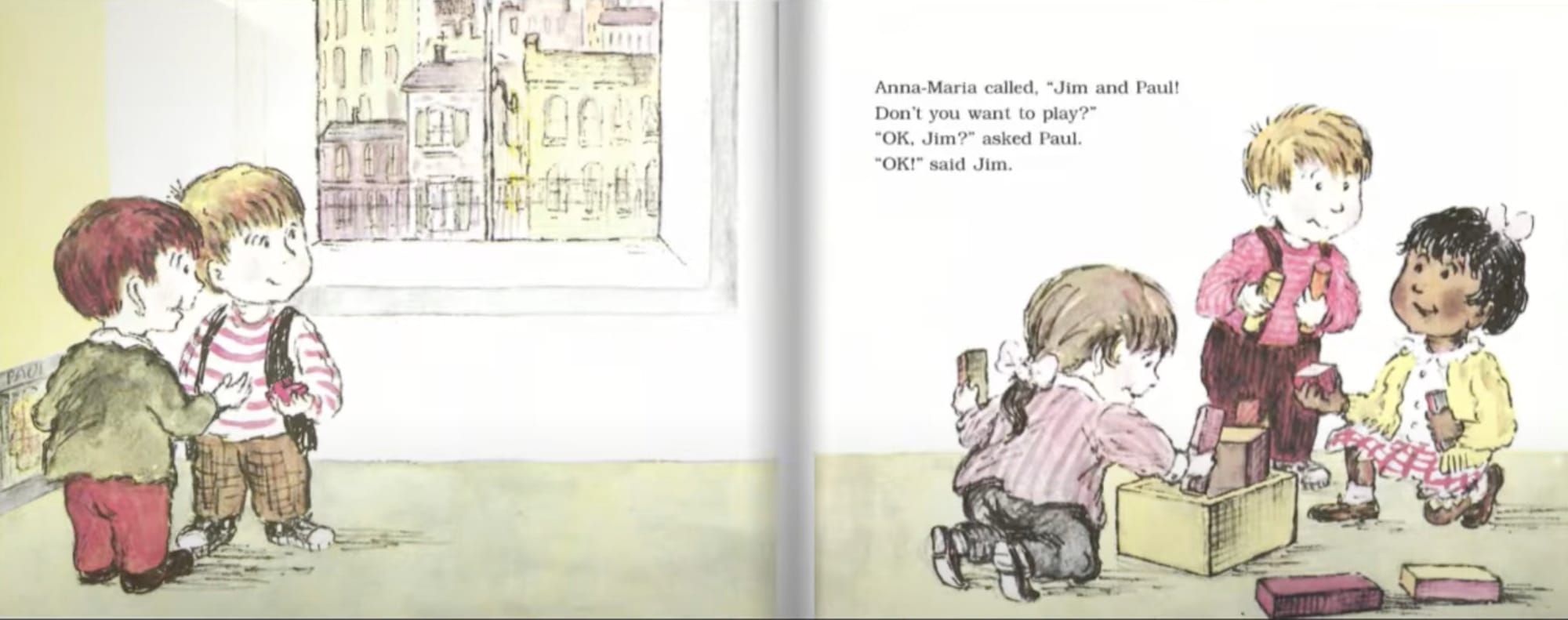

Will I Have a Friend?, a classic picture book published nearly sixty years ago, still articulates the core question at the heart of the experience of coming into a new community at any age. The question the title asks tugs at our desire to be assured of our own belonging and to know that we will, not only be welcomed, but have an ally if the social waters grow rough.

In all the genuinely necessary and important rallying cries for community, we would be wise to also bear in mind the crucial work of attending closely to the texture of our communities and to the lessons, long examined in school contexts, of the many forms social power can take. As good teachers do every year in these first weeks of fall, we should attend to the structures and habits that shape welcoming communities, and we should also be alert to the structures and habits that shape communities defined, instead, by fear of exclusion or rejection.

In the school context—and I think in the broader social context as well—understanding how and why communities marred by bullying develop is an essential first step toward understanding how we nurture communities that are inviting and supportive. Understanding the social tendencies that enable bullying is just as central as understanding empathy to establishing caring communities. Additionally, in a social and political climate where a key role of community is to offer protection from emboldened institutional bullies, considering how these power dynamics take shape is essential.

A common misunderstanding of bullying, which has been called into question by decades of research at this point, is the notion that bullying behavior stems from insecurity and lack of self-esteem. In fact, much of the research shows the opposite. While some children and teens, who exhibit bullying behavior, are considered bully-victims, occupying a precarious place in social hierarchies, where they find themselves moving between power dynamics, it is most common for those who act as bullies to show high levels of individual confidence and social popularity. In other words, human social systems have a tendency to reward aggression, authority, and even the victimization of others, and those who leverage such tendencies are usually alert to and empowered by these rewards, not lashing out to overcome their own uncertainty or vulnerability.

I’ve written often about our deeply rooted capacity for empathy. The propensity to reward and elevate bullying behavior does not negate the reality of our empathetic capacity. But the draw toward care and the draw toward power are both part of the complex evolution of our social inclinations. We are equipped to seek connection and compassion from our earliest years, and we also easily gravitate toward the tantalizing security that power seems to offer. Each of these inclinations informs the dynamics of a community and the ways in which we operate as individuals within those communities.

Over time, as the school research increasingly began to show that bullying behaviors were more likely to be carried out by those with high self-esteem than by those motivated by insecurity, and as it became increasingly clear that such behaviors often carry significant social reward, the approach to reducing bullying in schools shifted. The research revealed that, in order to effectively target bullying behavior and establish more welcoming school communities, the community itself needed to be the primary focus, not the ego of the bully. The most effective programs, designed to reduce bullying in schools, focus on addressing community-wide dynamics by actively fostering a positive climate and a spirit of inclusion, and by teaching children and adults strategies for protecting targeted individuals and rewarding community care. The primary goal in these interventions is to increase the social reward within a community for acting with compassion, and to decrease the social reward for acting to demean, exclude, or cause harm by leveraging power.

When I think about the most important practices that marked the beginning of each school year for me, they were the practices that helped all of us—adults and children alike—get to know each other, and the ones that planted the seeds for habits of care. In bridging these classroom understandings to our adult contexts, I’m especially drawn to the communities that emerge around mutual aid and protection. As I mentioned last week, I also like Garrett Bucks’ insistence on potlucks and soup parties. When the origin point of community is care, we set the bar for how a collective sense of welcome is established and sustained, how authority might be distributed rather than leveraged, and how we can anchor our interactions in webs of support rather than in hierarchies that prioritize power, compliance, or conformity over compassion.

Communities can be defined by how we open doors or by how we close them. While the well of empathy runs deep in the human heart and nervous system, the inclination to gravitate to power and dominance does as well. Both tendencies can shape our communities, and when we are on the inside, it can be surprisingly hard to notice which tendency is the source of our sense of connection. In an age of screens, overstimulation, and often-anonymous engagement with strangers, gathering with others and building deep communal relationships is important. But examining the texture and intention of those gatherings is also important. Community is powerful and, like all powerful forces, it is not inherently good or bad. Community is what we make of it and how we choose to enact it.

As children are busy in classrooms and on playgrounds across the country, forming new relationships and defining the terms of their communities in these early autumn weeks, I encourage you to take up the challenge as well and to look closely at your own communities.

To what extent are the spaces you gather in shaped by care and to what extent are they shaped by power? How do you weave new neighbors and strangers into your own social webs? Where do you find a sense of belonging and how can you extend that feeling more broadly? How do your communities regard those at the center and those on the outskirts? How do you nourish and protect one another, and how do you offer that nourishment to others?

Wishing you an open seat at the lunch table and the attentiveness and care to make space for someone else,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- Some thoughts from prior Notes on Hope messages about community and bullying: Creating Safety in Unsafe Times and The Power of Us

- Resources for Banned Books Week:

Reading Rainbow is back!

Censorship By the Numbers

Free printable bookmarks to engage others in the fight against banned books

The Legendary Children's Librarian of Harlem - I often write here about the essential role that holding harsh truths must play in fighting for hope. While last week's violent raid on a Chicago apartment building is extremely painful to process—especially the treatment of children—honestly taking in the reality it reveals is crucial to our ability to work toward a different future. If you haven't read about this incident, I urge you to do so.

A Massive Raid on a Chicago Apartment Building