I’d Like to Tell You About What Minnesota Nice Really Means

And the ruggedness that grows from habits of care

“And Yet

there comes a time when you stop hoping for

One American Hero

and realize there is only you—

picking trash from the neighbor’s yard,

hauling jars to the recycle bin,

calling your great-aunt Susan even though

she is not just your aunt Susan and

this is not just your godforsaken earth.

It is depressing to know a war is coming.

Worse to know the war will always be in you.

Little cauldron, little tender loon.

Take comfort in your bold heart

where hope and fear are mingling.”

~Kate Baer

I’ve spent most of my life in New York, where neighbor means the intimacy of knowing the daily routines and rhythms of the family next door, through the creaks in your shared floorboards and the wafting scent of each slice of burnt toast or simmering pot of soup. Here, in this crowded city, neighbor also means learning to surf tides of other bodies, as you move together and around each other—learning the shared signals that open a seat for the person who needs one on a crowded subway or that carve a path toward the door at your own stop. We have a reputation, in New York, for being tough and brisk, but I’m often astonished by all the ways we pay constant, quiet attention to one another. It’s how we make the dance of our intense proximity livable.

When I was a kid visiting Minnesota, where both of my parents grew up, my crowded, gritty New York life often seemed baffling to people there. The pace, noise, and lack of space must have seemed claustrophobic and intrusive to those accustomed to wide open skies and swaths of corn fields and lake water. Even in the cities in Minnesota, many of the streets feel wider, and the urban landscape is dotted with bodies water and shaped by the banks of the Mississippi.

Being a good neighbor in New York often means taking care to avoid disrupting other people whenever possible—gingerly stepping around their grocery bag on the bus or walking as softly as you can, in stockinged feet, down the hall of your own home, mindful of those whose ceiling is your floor. Being a good neighbor in Minnesota is, in many ways, the opposite, I think. It is a welcoming in, an intentional call to share space when neighbors are more often found across a driveway or a street or even on the other side of a field or a lake. It’s keeping a pot of coffee hot in case someone stops by. These are different ways of attending to each other, but both are forms of ingrained, habitual community care. I think moving between these landscapes and communities as a child helped me learn to recognize care in a multiplicity of varied gestures as an adult. There are many ways to share space and to look out for each other.

Just as people in Minnesota were often incredulous about the apparent anonymity and perceived dangers they thought marked my life in New York, New Yorkers would often express skepticism about the superficiality that they presumed was the guiding force behind the consciously friendly habits of so-called "Minnesota Nice.” Where New Yorkers have a reputation for being tough and brazen, midwesterners, especially Minnesotans, have a reputation for being nice. And in New York the notion of niceness often translates to an assumption of falseness or a discomfort with direct communication. There can be a belief here that a cultural norm of niceness must really translate to either timidness or passive aggressiveness in practice. It must be different from genuine kindness. But in my experience of both New York and Minnesota, neither of these perceptions really hits the mark. New Yorkers are more caring than their reputation would have you believe. And Minnesotans are more sincere and pragmatic in their care than the reputation for surface-level niceness belies.

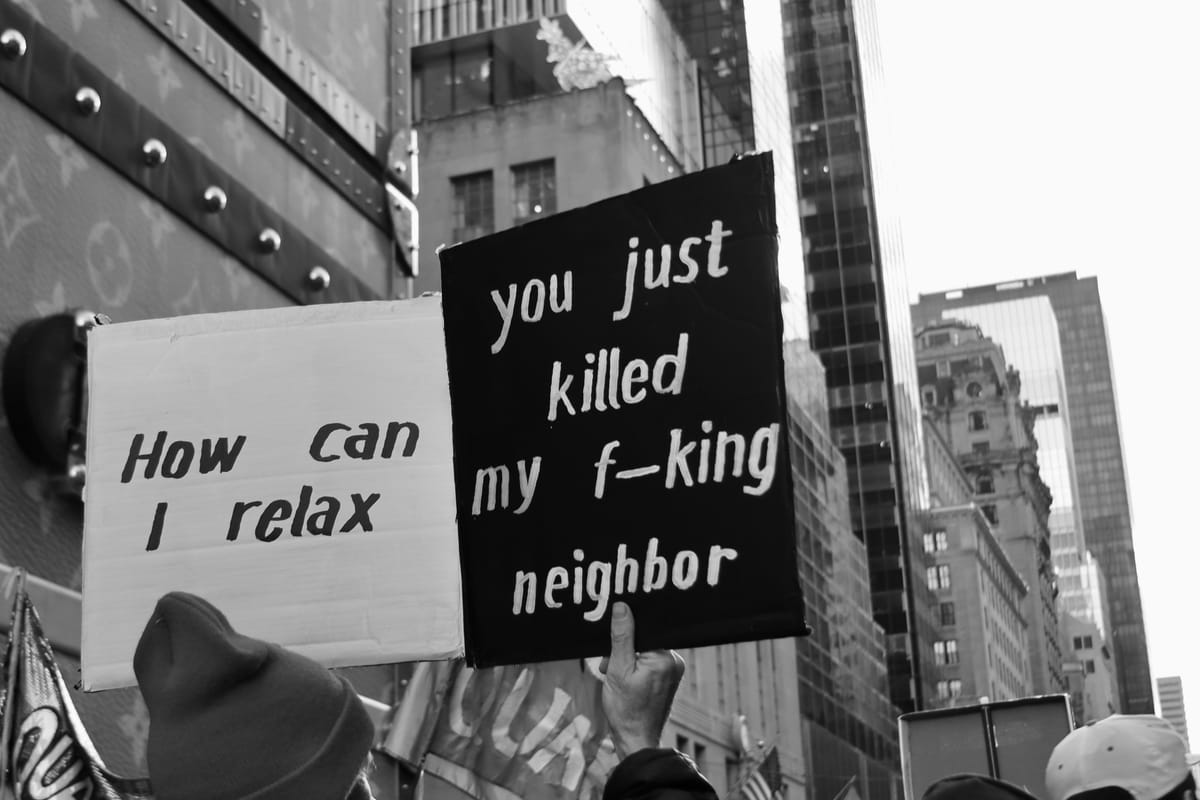

Assumptions about Minnesota Nice have made it surprising for some, watching from afar, to witness the fierceness with which Minnesotans are protecting each other now. Some of the muscles and the practical organizing networks for the current moment were surely built during the 2020 George Floyd protests. In fact, when it comes to everything from convening protests to managing child care while schools are closed, and delivering groceries to those who fear leaving their homes, the skills and connections developed six years ago appear to have been very directly reactivated this week in Minneapolis. It’s also worth noting that Renee Good’s killing isn’t the first shocking act of violence in Minnesota even in more recent months. The state just experienced the murder of Melissa Hortman and the attempted murder of John Hoffman in June.

All of this very recent history provides vital context for the past week’s rapid community mobilization. But I also think that, to understand the response in Minnesota right now, it is helpful to have a deeper understanding of what Minnesota Nice really means in practice, because in my experience it is neither timid nor false. It is, however, extremely practical and results-oriented. The niceness that Minnesotans are famous for is primarily about deeds not words. This is why I’ve always found the external, sometimes negative, perception perplexing. Minnesotans aren’t particularly prone to the effusive language that might signal hollowness or hypocrisy in another context. This isn't what nice means there. If over-the-top friendliness or shallow social niceties is how you envision Minnesota Nice, you’ve probably never been to Minnesota—especially not in the winter. In real day-to-day life, Minnesota Nice is much more likely to show up as a neighbor, or even a stranger, helping you shovel your car out of a ditch, stacking sandbags before a storm, or caring for your kids. Minnesota neighbors might even do these things without saying very much at all.

“A little over a year ago, I was driving back from Duluth with a couple non-Minnesotan Macalester students. I got a flat tire outside the Twin Cities and my carjack was broken. ‘Should we call AAA?’ they asked. I was dumbfounded. This is Minnesota! I knew someone would just pull over and help. I was met with skepticism, but within minutes, two cars stopped to help.”

Similarly, years ago, when my dad and I were in a car accident in Minnesota on a bitterly cold December afternoon, strangers quickly showed up to not just offer help but to quietly insist on it. While we waited in the snow, with the occupants of the other car, for emergency personnel to arrive, a mother in a minivan pulled over and directed us all to pile into her car while we waited. “It’s freezing,” she said, “You can’t stand out here. Come on in.” Her daughter climbed into my lap, because there wasn’t really room for all of us, and we waited—strangers huddled together in the warm air of her car’s heater. Her children didn't seem rattled or perplexed that this was happening, because this kind of practical assistance is a way of life in Minnesota, especially on the coldest days. These kinds of gestures are the expectation, not an exception. And they are not limited to the people you know well. If you are standing in the cold in Minnesota, someone you’ve never met will likely insist you get into their car.

As the Macalester article also explains, this is a feature of Minnesota’s unusual amalgam of political policies, too, which I've found aren’t really seen as partisan by many of the states’ motley crew of pragmatically-minded voters. Care, even political care, is practical. It's about meeting needs. This doesn’t mean everyone always agrees. But it has, nonetheless, resulted in unusually strong systems of social support.

“Minnesota Nice is also thought to fuel Minnesota’s distinctive progressive and populist values. Whereas many other parts of the U.S. function generally as a meritocracy, Minnesotans tend to privilege egalitarianism and humility. This has manifested in our unique political climate and strong education and health care systems.”

Minnesota Nice doesn’t come with a lot of flourish or fanfare. But it gets the job done and that’s the point. No one gets left out in the cold for long.

This is why it doesn’t surprise me to see Minnesotans flooding the streets with such ferocity, blowing whistles, hurling snowballs, forming human chains outside schools, and delivering food to each other. As reporter, Jack Jenkins noted,

“I’ve reported on ICE watchers in other cities, but I’ve been struck by just the sheer number of people I’m encountering out here who are publicly participating in ICE observation.”

When habits of care are so engrained in daily life that they practically make AAA irrelevant, stepping out into the street when your neighbor is in trouble doesn’t seem like as much of a stretch. When it’s normal to keep coffee hot and extra cookies in the cabinet just in case someone drops by unexpectedly, creating food chains to deliver groceries to those who can’t risk leaving their homes is an easier extension.

This isn’t to say any of what Minnesota is going through right now is easy. I’m especially worried about children, particularly as schools and child care have been a central focus for the current federal aggression toward the state. I’m worried about the lasting trauma of the fear and violence these kids are experiencing in the same way I worry about children living through active military incursions—which is essentially what is happening. I worry about the children whose families are being targeted by the government, and about the ways in which this can bleed into classroom life. As much as I believe a culture of practical, habitual care is playing a role in the extent to which many Minnesotans are standing up for each other, including for their immigrant neighbors, this doesn't mean that there isn’t also entrenched racism in Minnesota, as there is everywhere. Some Somali families are reporting that their children are being taunted in school, in addition to fearing their parents and older siblings could be taken at any moment. All of these experiences will undoubtedly leave deep scars.

But the flicker of hope I’m able to locate in all of this is in the models of courage and care that children are also witnessing every day, as parents and teachers and community members stand up for them, for their friends, and for their neighbors.

I desperately want children’s yards and classrooms to feel safe again—their days filled with learning and play, as every child’s days should be. There is no easy way to know how best to care for children amidst these kinds of threats. But, to the Minnesota adults, who are taking enormous risks to care for each other and to protect each other, please know that, as much as your children should not have to experience any of this fear, they are also witnessing your compassion and your courage, and they are learning from that, too. And the rest of the country is also learning as we observe your bravery, just as we’ve all learned from L.A. and Chicago and Portland already. We are all being made braver and kinder and more prepared by your model. May we all live up to the grit and determination and pragmatic kindness of Minnesota Nice, even in the face of these most difficult tests.

Wishing us all courage, compassion, and the kind of care that can be found among New Yorkers on the subway or among Minnesota neighbors in the snow,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- Minneapolis Knows How to Resist This State Violence

- Thomas Merton's Letter to a Young Activist

- On Learning About Yourself From Your Community

- Care, Unlike Terror, Is a Renewable Resource

There are good resources for helping Minnesota at the end of this essay. - 2026 Trans Girl Scouts to Order Cookes From!

This is seriously one of my favorite annual traditions. Learning about each of the individual kids and ordering their cookies makes me markedly happier and more hopeful. Sometimes it's the little things.