Remembering Lucille Bridges, Who Held Ruby’s Hand

And why we can’t afford to leave adults out of the frame of children's history

“My god,

I thought, my whole life I’ve been under her

raincoat thinking it was somehow a marvel

that I never got wet.”

~Ada Limón

Last week marked the 65th anniversary of school desegregation in New Orleans—or as you more likely think of it, the day Ruby Bridges first walked into William Frantz Elementary School, escorted by Federal Marshals. In fact, there were four six-year-old girls, who braved threatening crowds of protestors and empty classrooms in New Orleans that morning, and in the weeks following. Each of them were, at once, small children just trying to go to school and unlikely leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

We tend to think only of Ruby as the emblem of this pivotal moment, probably because she was the solitary Black child to start first grade at her school, and there is something uniquely striking about her small, lone figure, whereas the other three—Leona Tate, Tessie Provost, and Gail Etienne—at least had each other at McDonogh 19 Elementary School. It is, nonetheless, difficult to imagine how any of them made sense of the rage directed at them for simply trying to learn. As Gail Etienne recalls, “I really thought that if they could get to me, they’d want to kill me. I didn’t know why. What had I done? I was just going to school.”

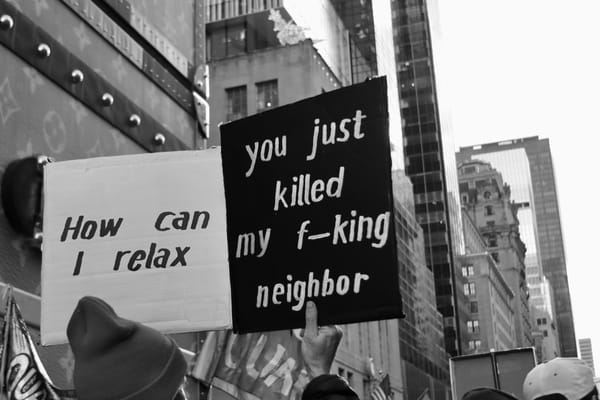

There is something particularly foreboding about considering the terror and isolation all four of these very young children faced in the context of our current moment. Their undeniable bravery in the mere act of going to school each day feels uncomfortably familiar yet again, as stories surface of teachers and parents needing to create barricades and whistle patrols to protect children entering and leaving school from ICE agents, or of daycare teachers being ripped out of their classrooms by armed agents in front of the toddlers they care for, or of a baby being pepper sprayed. School should never be a zone of terror for children—nowhere should be, actually, but certainly not school—and we will surely fail to protect children today if we imagine that the path four little girls heroically paved in 1960 cannot be easily undone.

As echoes of the same vitriol that Ruby Bridges and Gail Etienne and her friends endured 65 years ago seem to reverberate across the steps of school buildings and daycares again today, it is important to reckon with the fear that continues to mark too many children’s days and the bravery we often require of the very young.

But it is also important, I think, to remember and reflect on what the adults were doing, as these courageous children started school. It is tempting to focus our gaze only on the children, and, indeed, the photos that have come to hold this time in history in our memories do just that. I suspect that this is because looking only at the bravery of children allows us to feel a sense of admiration and inspiration without the more difficult feeling of a call to personal accountability. It is especially easy to find compassion and awe in the image of a small, brave child when we don’t have to grapple with seeing a reflection of ourselves in the frame as well, asking us to consider what role we might have played as the adults then and what role we might play in a similar position today.

Ruby Bridges and the other children who walked to school that day demonstrated profound courage, and it is important to continue to learn from them, especially as we still ask so many children to be braver than they ought to need to be today. But other images exist that tell a wider narrative, and one it is equally important for us to learn from, as we decide what we as adults will do to protect children who are threatened today—immigrant children, trans children, Black and brown children, and disabled children, in particular. When children have to be harrowingly brave, it is always a sign of the failure of systems beyond their control and ought to be a clarion call to our own adult responsibility.

It was my own son who reminded me of this as he was also just beginning elementary school, when he asked me a question about a photo of Ruby Bridges that stopped me in my tracks. I spoke about his question and the research we did together to answer it, in the opening remarks of a forum for teachers in 2017. We called the forum Teaching in Urgent Times, and if anything the times feel only more urgent now, and the question of what our adult role ought to be seems even more pressing. So, today I’m re-sharing those remarks here in the hope that a five-year-old’s question and the answers we found might be helpful again, if only as a small starting point for your own courage.

I am struck, in re-reading these remarks, by two things that feel notably different today compared to 2017. At the time, I was observing a trend in centering the strength and the rebelliousness of children as an emblem of hope for adults, whereas now we find ourselves fearful of a crisis in pediatric mental health (though the children are still leading bravely in many ways). Additionally, teachers were not nearly as restricted in the materials and topics they felt comfortable exploring with students in 2017, as they often are now.

The threats children, teachers, and parents are facing have surely evolved in the eight years since I gave these remarks. In many ways, the world is even scarier, and children are even more at risk. But I think these changes only make it more essential for us to ensure we are focusing our gaze, not only on the inspiration of brave children but also on the adults around them—challenging ourselves to live up to the courage of Ruby, Leona, Tessie, and Gail, as well as the adults who held their hands.

Walking with Children

Opening Remarks, Teaching in Urgent Times Forum

Bank Street College of Education, 2017

Whenever we face significant ruptures, be they intimate breaches within communities or larger environmental, social, or political upheavals, those of us who spend our days with children are confronted with questions. How much of the outside world do we invite into our relationships with children and how much do we attempt to hold at bay? What does it mean for a classroom to be a safe place?

It is often our inclination to be protectors in these moments: to shut our doors and pull our blinds; to bolster ourselves in curriculum that feels familiar, if removed; to make our classrooms into shelters. These were the themes of conversations among parents and teachers in the fall, and they have echoed on college campuses in debates over the role of safety and sanctuary in learning and the navigation of hate speech in educational contexts.

And yet, in this particular moment, something different seems to be happening to our conception of the role of children, particularly young children. Images of children as powerful defenders of their own future have captured our imagination. Book lists for little rebels and dissenters have circulated. The Fearless Girl confronts The Bull on Wall Street, while a little boy in a hoodie commands a firing squad to stand down in Beyoncé’s Formation. Adults have been emboldened by these images of young bravery. Perhaps the future seems less paralyzing when we can see it embodied in a confident and defiant child, holding their ground. We are offered a reassuring sense of moral clarity in complex times. Children become symbols of hope and innocence for us, and so, perhaps, their apparent triumph in the face of extreme power makes us all feel less small.

This is important and may be a particularly appealing notion for educators. We believe deeply in the capacities of children and devote ourselves to helping them find their voices and realize their potential.

It was with this mindset that I found myself, a few months ago, sitting on the floor, reading a book with my own kindergarten son about Ruby Bridges. When we arrived at the picture of Ruby in her white dress—small but purposeful, surrounded by the limbs of adult men, and yet somehow seeming to lead the way herself—he stopped. He sat silently looking at the page for a long time with an intensely furrowed brow, hands planted on either side of the book. I wondered if he felt worried about Ruby or impressed by her? Finally, still staring at the picture, he asked incredulously, “Where is her Mom?” I realized that I wasn’t sure and pointed out the U.S. Marshals protecting her, my default instinct to reassure him that adults were present, keeping her safe. But this was insufficient. To his five-year-old eye, a child without a trusted grown-up is alone, no matter how many strong, anonymous officials surround her.

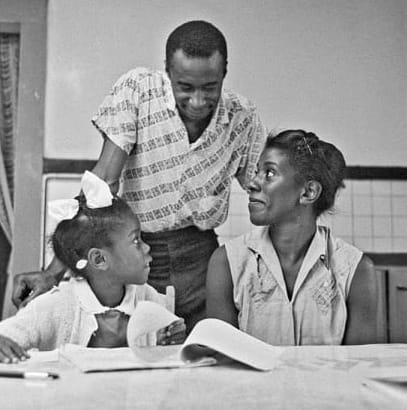

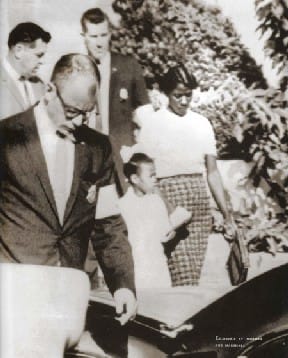

So, we embarked on a mission to learn where Ruby’s mom had been. We found her, Lucille Bridges, in the one picture book in which Ruby Bridges tells her own story. And, as it turns out, Lucille Bridges was holding Ruby’s hand.

Ruby’s mother did accompany her to school at the beginning. Lucille Bridges even stayed in school with her daughter for the first two days, until Ruby had met and developed some rapport with her teacher, Barbara Henry—a transition process familiar to those of us who work with young children. Throughout her own narrative, it is not the Federal Marshals or even the angry crowds who figure most prominently in Ruby’s memories. It is her mother and her teacher who surface again and again in her retelling. And yet, the images of Ruby walking hand in hand with her mother on her first days of school, or standing at the black board beside her teacher, are not the ones that typically represent this moment in history. We are captivated instead by the image of a little girl, brave and seemingly alone.

As we consider our role as adults and our relationships to children in times of upheaval, let’s take a moment to refocus our gaze and to find hope and power in these images of a child and a trusted adult walking together.

Progressive teaching is often viewed by critics as an approach that either leaves children to their own, chaotic devices or somehow indoctrinates them. But nothing could be farther from the truth. Progressive pedagogy challenges us to engage with children in a co-creation of knowledge, to explore the world side by side. We neither shield children from the world, nor do we expect them to confront the world entirely on their own. This walking together is at the core of our work.

Teaching is challenging at any time. It becomes more so when we are feeling overwhelmed in our adult roles, inundated by daily news feeds and struggling to redefine our own adult identities, as we locate a new social or political voice. How then do we support and guide children when we are having difficulty finding our own footing?

Ruby’s mother and teacher offer us some guidance here as well. They have both spoken openly of their own fear and of the intensity and ugliness of the world around them as Ruby started school. Yet, Mrs. Henry goes on to say of her year teaching Ruby, “Neither one of us ever missed a day. It was important to keep going.”

Let us remember these words as we engage in the work of keeping going, of finding entry points, of making meaning with children, and of locating our own courage, even in the most difficult moments.

“On Sunday November 13th, my mother told me I would start at a new school the next day. She hinted there could be something unusual about it, but she didn’t explain. ‘There might be a lot of people outside the school,’ she said. ‘But you don’t need to be afraid. I’ll be with you.’”

~Ruby Bridges, Through My Eyes

Wishing you the courage to walk with children today and the fortitude to insist on a better tomorrow,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- The Shocking Truth About Gen Z Voters Is That They're Pretty Great

- Why Clergy Should Risk Assault to Protest ICE by Reverend Michael Woolf

- Action Against Injustice: How to (Quickly) Get Started, Restarted or Unstuck

- Meet the NJ Librarian Who’s Taking on the Culture Wars

- Indie Bookstores Merge Activism and Literature for Collective Care