The Butterflies Are Losing Their Colors

What we have to let go of if we want to live vibrant lives

“The trees keep whispering

peace, peace, and the birds

in the shallows are full of the

bodies of small fish and are

content. They open their wings

so easily, and fly. It is still

possible."

~Mary Oliver

I read recently about a research project in the Amazon that has been documenting the impact of deforestation through the loss of color in butterflies’ wings. As wild rainforests are replaced with plantations that grow a singular species like eucalyptus, the natural advantages of vibrant colors seem to be slipping away. The path to survival for the butterflies becomes one of neutrality and discoloration instead of diversity and brilliance, and the impact has been more rapid and more demonstrable than the researchers anticipated. The disappearance of color among butterflies appears to be an indicator of the loss of complexity in their ecosystems and is observable across other species and ecosystems as well. It seems we are literally draining the world of color. Phoebe Weston, writing about this research, explains,

“Colour isn’t just about aesthetics, it has important evolutionary functions. In a broader trend, ecosystems that once supported many colours are becoming more muted as they are degraded, simplified and polluted by humans. Coral reefs are bleaching, oceans are becoming greener – even rainbows are predicted to become less visible in densely populated and polluted areas.”

We’re losing rainbows. The practical explanations for all of this loss of color are simple: a combination of pollution and human encroachment into wild spaces in pursuit of mass produced convenience has decimated much of the natural world, from the depths of the oceans to the canopies of the rainforests. A less wild world is a less complex world, and a less complex world is a less colorful world. We can see this in urban environments, too, where the reach of skyscrapers, higher and higher into the clouds, has cast increasingly long shadows over everything below, muting the vibrancy of the trees, even while reflecting images of those very trees in pristine windows, tricking the birds into thinking they are flying toward a forest, not toward a collision with glass and steel.

Beneath these very real and literal causes for the greying of our world, there are, of course, layers of value propositions, most of which are rooted in the pursuit of wealth, comfort, and expedience and all of which easily blind us to any collateral damage. But, as I was reading about the butterflies, I also found myself wondering if there is an even simpler trade-off lurking beneath all these very post-industrial ideals of mass accumulation.

The brilliant and varied coloration of the butterflies is a direct result of the complexity that wildness creates. A wild, inherently uncontrolled environment develops unpredictably and in many directions at once. Wildness is, by definition, untamed and it is the very complexity that results from this lack of control that produces the butterflies’ bright and varied colors. In order to be rewarded with a world that offers us a wide and vivid spectrum, we have to be willing to tolerate the chaotic and unpredictable forces that nurture a diversity of unanticipated outcomes. And humans are not especially good at tolerating chaos. We more often strive for control and order. Weston notes,

“Whether dazzlingly red, deep green or ghostly pale, the richness of a tropical forest provides butterflies with a diversity of habitats in which to communicate, camouflage and reproduce. As humans replace tropical forests with environments such as eucalyptus monocultures, however, those requirements are changing. In a plantation, the ecological backdrop is stripped bare and drab species do better. Being bland – like your surroundings – becomes an advantage.”

On a basic level, the proliferation of monoculture plantations, and by extension the loss of butterfly colors, is a direct result of our reliance on easy access to things that now seem fundamental to our day-to-day lives, from inexpensive furniture to toilet paper. And eucalyptus is an especially interesting example, because it’s often presented as a sustainable material. It is fast growing and requires less water and pesticide use compared to other similar resources. But anything that grows under the highly controlled, human constraints of a plantation, rather than the multiplicity of natural variables present in a forest, replaces the complexity of wilderness with a landscape that is simple, predictable, and uniform. And, as with all taming, this drive to control the uncontrollable and to transform mystery into order leaves us with a world that we may feel in charge of, but that is also less alive.

The price for a world that is filled with startling beauty and variety and even color itself—even rainbows—is loss of control. Evolution, as it occurs naturally, is largely a matter of serendipity across time, scale, and immensely varied circumstances and influences. This natural serendipity within complex systems yields a stunning range of lifeforms. By contrast, when we replace the unpredictability of the wild with tidy plans and constructed systems, we trade the spectrum of life for one in which it is biologically advantageous to be bland, to blend in, and to become one with the monoculture.

The solutions on an environmental or a personal level aren’t easy. We have been making choices for centuries that have led to an increasingly constrained and therefore bland and uniform world. I don’t expect, for example, that we will somehow just give up our reliance on toilet paper or coffee to embrace a mass, global-scale re-wilding or a return to pre-agrarian, pre-industrial life. Though there are many indigenous communities actively developing and advocating for ways of striking a better balance between the natural world and the economic world.

But, as we face the possibility of a world with less color, I think it is worth considering our relationship, not only with possessions and conveniences, but also with our fundamental human passion for power, for controlling anything that seems unpredictable or divergent, and for taming anything that seems to operate beyond the reach of our orderly systems.

As the environmental journalist, Megan Mayhew Bergman, wrote recently,

“Westerners could admit at any point that we have misread our place in the cosmos and shift toward this older, still living worldview: humans not as commanders of the natural world but as kin, interconnected equals among other beings and systems.

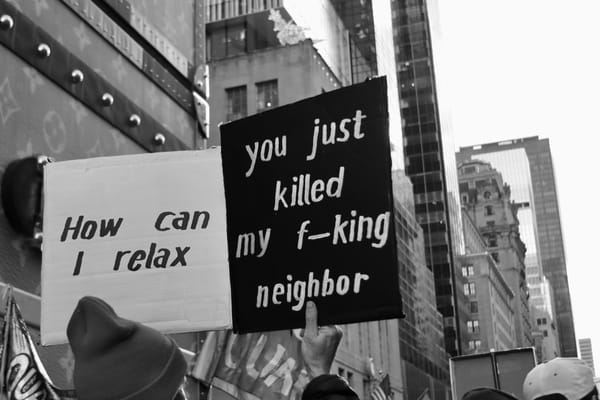

This suggestion might sound sentimental and naive in a political moment when even extending compassion to other humans meets resistance. Refugees are being turned away at ports of entry – grim proof of how easily our empathy falters. But new ideas are hard precisely because they threaten the story that keeps our lives coherent.”

These are difficult frames to renegotiate, both as individuals and on a wider cultural level. As we constantly “innovate” toward hyper-automated lives that allow us to control and curate every detail of our days, it is surely becoming more challenging to remain open to complexities we can’t cultivate and to tolerate change that is more dynamic than our ability to make calculations and predictions.

We train ourselves, day in and day out, to desire and establish a high level of control over the most minute, mundane aspects of our lives. But the cost for all this control is high. As we reign in the natural world and even attempt to constrain the simple spontaneity of being in community with other diverse, unpredictable, varied humans—and, at times, with our own unpredictable hearts and minds—we make sacrifices that are felt in both intimate and global ways.

We will have to ask ourselves what stories we plan to tell our children about the past when the butterflies are all beige? How will their imaginations and their sense of wonder and possibility be constrained by growing up into a world with less and less color and variety? How will their understanding of themselves be limited if it is increasingly advantageous to be indistinguishable from a colorless world?

Last week, I was waiting at a bus stop when a child standing nearby asked his father if an octopus can change color. It was the kind of seemingly random question that children often pose, as their minds sift through all the novel information and experiences of their days, getting to know the world. What might the answer to this question be if we continue to cultivate environments that are so controlled there’s no need for color? How much curiosity will we drain as we make the world ever more uniform?

It is hard, as Bergman notes, to radically rethink our way of life and our self-perception as an exceptional species meant to dominate and shape the world we live in. But the butterflies do offer us a little encouragement here, in addition to their warnings. While they can lose their color quickly in response to environmental changes, the butterflies also appear to regain their color readily when we permit their habitats to become wild again. In areas of the rainforest that have been allowed to regenerate, the diversity of butterfly coloration has returned. It's not too late to choose to live in a colorful world.

The first step, I think, in addition to reevaluating our material choices, must be to look honestly at our attachment to control and our willingness to be surprised by the diversity of a world we don’t dominate so ruthlessly and methodically. If we can choose to let a little more serendipity and wildness into our days, even in small ways, perhaps we will also be able to reshape our desire for control in other, bigger ways and allow the colors of unknown evolutions yet to be discovered to unfold.

In the familiar words of Wendell Berry,

“When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.”

Wishing you the serendipity of wildness, the freedom to rest, and the gift of colorful days,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- The Playbook of Every Successful Nonviolent Struggle

- Childcare Workers Are Building a Network of Resistance

- How Libraries Are Enlarging the Civic Infrastructure

- New Yorkers Stock Up on Whistles

More from Notes on Hope...

- A few other places I've written about our relationship with the natural world: A Love Letter to Jane Goodall; What Will You Save?; Look for Small Sparks of Joy; How We Endure; A Love Worth Fighting For; and I Carry Your Heart.

- And, finally, if Thanksgiving is a tricky holiday for you, I get it. I wrote about navigating this time of year last November and I'm relinking that note here, in case it's helpful to you this week.