The Promise Teachers Make

And what we can all learn from the fierceness of their commitment

May we raise children

who love the unloved

things—the dandelion, worms

and spiderlings.

Children who sense

the rose needs the thorn

and run into rainswept days

the same way they

turn towards sun…

And when they’re grown and someone

has to speak for those

who have no voice

may they draw upon that

wilder bond, those days of

tending tender things

and be the ones.

~Nicolette Sowder

The first weeks of the school year in an early childhood classroom are not about letters and numbers or blocks and play-dough. There is all of that, of course. But really these first weeks are about trust. We often describe the start of school as a process of separation for young children, because, as they step into the classroom, they are learning to step away from their first and most secure caregivers. But having spent years navigating this delicate transition with children, I’ve come to think that “separation” is not the right word to use, because when this process is handled well it revolves entirely around connection.

When we think about this phase in a child’s life as one of separation, we place the burden on the child to step over the threshold and away from everything they have learned so far about safety and about the contexts in which curiosity and exploration are possible. In this formulation, we orient growth and learning around establishing resilience and independence, even from a child’s very first tentative school experience. It is a recipe for equating success with ruggedness and isolation, even though this is rarely the explicit intention, nor is it how we actually enact the process.

Instead, when we think of this experience as one of establishing connection and trust, we signal to children that their world is expanding, not contracting. We show them that there is even more care in the world than they knew, because they can find it in the infinite possibility of new adults and new friendships. And we also show children that those who care for them return—that while they may at first feel they are experiencing a separation, it is possible to remain connected to those we love by holding them in our minds when we are apart and by reuniting. The child’s world expands through a widening network of care and trust, not through fissures. And this occurs again and again, across each transition into new and wider communities as children grow.

We don’t always articulate the experience of guiding children into these ever widening communities in such relational terms, because, particularly in the U.S., it is more common to reflexively orient ourselves to frameworks of independence than to care. However, in all of my work with teachers over the years, I have seen that a deep and instinctual commitment to the trust that they establish with children almost always anchors their work. Nor is this something I’ve seen only in early childhood teachers. At all age levels, I have seen how firmly teachers root themselves in their commitment to care for, protect, and advocate for their students. If this were not the case, teachers wouldn’t continue to come to school despite the constant threats that land, again and again, at the classroom door.

If school were really entirely about children’s independence and resilience, or even if it were only about their progress toward metrics of achievement and learning, teachers would not routinely prepare to put their bodies between their students and a gun. Teachers would not have been willing to come to school masked and gloved, as a pandemic raged. And they would not be trying now to figure out how their active shooter training might also prepare them to protect their immigrant and trans students from newly imminent dangers.

At the most basic level, teaching is rooted in a sacred relational trust that is established anew each school year, in which we assure children, through our words and actions, that we will listen to them, that we will speak for them when their voices are too small or are deemed unworthy, and that we will protect them when they can’t protect themselves.

Several years ago, when I was the director of a preschool that used a local park for recess each day—as many schools in urban areas do because of limited space for on-site playgrounds—I asked our security director how teachers should prepare for the possibility of a shooting threat outside the school. We regularly ran security drills inside the school, and we had many protocols in place for keeping the children safe when they left the building. But we had never addressed this specific question directly, seemingly because there was not a good or viable answer. And, indeed, as soon as his answer came, I knew it would be impossible advice for both children and teachers to follow. He told me that the children should run away from their teacher and fan out in every direction. He suggested we compare this action to a flower or a star, bursting away from the central fixture of the teacher. By staying together, he explained, the class was a single, obvious target, but by spreading out the children would become individual moving targets, which would increase their chances of survival. I knew this would run counter to every instinct a child has, and perhaps even more critical, it would run counter to every instinct a teacher has. I am certain that it would be easier for most teachers to throw their own body over children than to push them away. These are not instructional choices or even simple safety procedures. They are unimaginable choices about the fierce love we want children to feel in moments of joy and in moments of fear. But they are choices teachers think about.

This is also why, as schools and teachers are being directed to follow executive orders that many know will cause harm to their students, either by stripping them of their identities or by overtly putting their lives in danger—and as many higher education institutions are expressing positions that claim either principled neutrality or powerless compliance—teachers, and in some cases state K-12 education departments, have been among the strongest voices of resistance and strategic organization.

At a very deep, personal level, while teachers are accustomed to adapting their instructional techniques and curriculum to shifting polices, most teachers hold an inviolable line when it comes to their students’ physical and emotional safety. Regardless of differing or evolving approaches to teaching, the core trust that is established with students feels sacred and deeply personal to most teachers. It is not something teachers necessarily think of as political or pedagogical. Rather, it is foundational to their internal knowledge that teaching—at least during the years when students do not yet have the rights or capacities of adults—is subject to a duty of care, just as the work of doctors is. This is not a commitment that allows for neutrality, nor is it something to be handed over lightly.

Teachers don’t merely impart knowledge, and their work can’t be reduced to this when it is convenient, even as so much more is routinely asked of them. Teachers put personal wellbeing to the side every day to care for students, whether it is through the simple act of comforting a sick child or the more unthinkable act of barricading a door from an active shooter. I’ve argued previously that, in a society that truly prioritizes children, teachers should not need to be heroes. But we certainly can’t expect teachers to defend children’s lives at great risk to their own and then asterisks that responsibility with clauses that limit which students they are supposed to care for and which students they should be prepared to sacrifice.

There are times when it is appropriate for teachers to convey neutrality. If we aim for children to become critical thinkers, who can assess information and synthesize complex ideas, sometimes we have to hold our own ideas back so students have the space and the agency to develop and express their own thoughts. And if we seek to create educational environments where a range of students from varying backgrounds and experiences feel a sense of belonging, we have to be prepared to allow for differing ideas and perspectives. But this form of neutrality is a pedagogical strategy that is tied to students’ learning, not to their survival. It is applicable only after children’s mental and physical safety has been assured, because children do not learn when they are afraid or when they are trying to make themselves invisible.

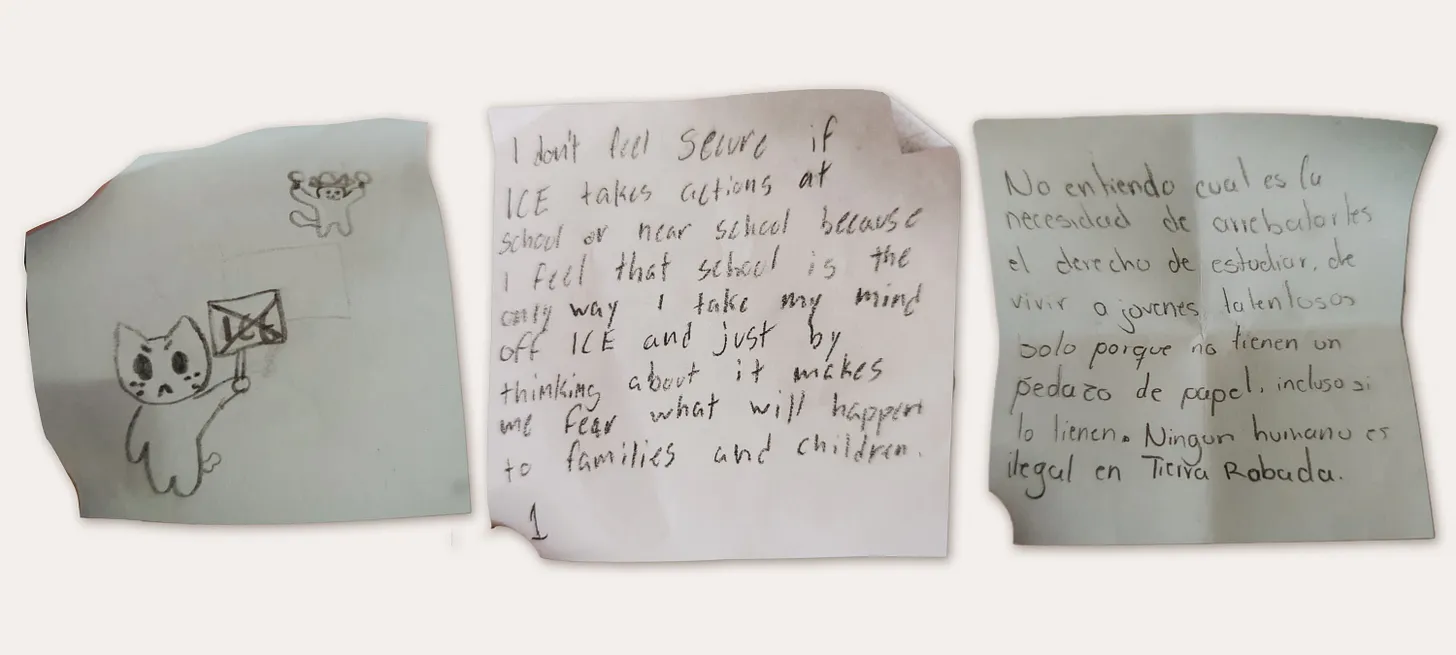

When we shuffle our students silently into a safe room, doing everything in our power to protect them from bullets, we are not operating in the realm of pedagogical choice, and there is no space for our neutrality here. When we defend the rights of our trans students to exist and be acknowledged for who they are, knowing that 82% of them will consider suicide, this is not an instructional choice. When we are left to consider how we will protect an immigrant child from an armed federal agent, there is no neutral option. Even when we commit to allowing children access to books that acknowledge their lived experience, we are working in the realm of survival not pedagogy, because reading can be just as life saving for a child who may be questioning their worth or their right to exist, as shielding them from a bullet.

These are not simply instructional choices. They are the deepest enactment of the promise we make at the start of each school year, when we assure our students that they can trust us and that we will care for them, while they are in our classroom, as if they were our own. It is the promise I hope my son’s teachers make on his behalf and that of every other student in his class every day.

We often idealize children’s capacity to change the world for the better, particularly when we are feeling the most unable to do so as adults. But we cannot expect children to take responsibility for repairing the world in the future, if we aren’t willing to show them that we care about their experience of the world today. We can’t expect children to care for others, if we haven’t shown them what it feels like to be deeply and unconditionally cared for. It is our responsibility now, as the adults who promise children that they are safe with us, to make good on that promise, so they will do the same for others one day.

I’ve been watching this video of children singing, “All Is Full of Love,” on repeat over the past few weeks. I encourage you to listen. I think it encompasses the promise we make to children when they enter our classrooms, whether they are three or eighteen. It is a promise most teachers live, not through their textbooks, but in their souls. And it is a promise that we should all commit to sharing with teachers—to tend tender things and to speak for those who have no voice. I hope you will share that promise with me.

Wishing you a heart full of fierce and committed love,

Alicia

A few resources I found helpful & hopeful this week…

Thirty lonely but beautiful actions you can take right now

Safe Schools for Every Student

Find your place in: The Social Change Map

And buy cookies! I know I’ve included this link before. But I am so serious about how much this super simple way to support vulnerable kids has helped my outlook.

If you think someone else in your life might need some hope, please share. It’s always easier to hold onto hope when we’re not doing it alone.