We Need to Talk About Children’s Rights

And about the seductive mirage of parents’ rights

“I rise alone

and go to find my child

sleeping in his own arms in the darkness

and I kneel there, and I lay a hand

like a small rain on his trembling chest

and I feel his heart

as it croons its little music—

and I listen, I sit awake

and listen: this little heart

that sings the hymn

of living…”

~Joseph Fasano

I have a vivid memory, from early in my teaching career, of standing alone in a tiny back room, late in the day, printing photographs my class of three-year-olds had taken. We’d gone looking for signs of spring, and I’d given the children a camera to document their findings.

This memory remains so clear in my mind, because, as their images were enlarged by the printer, the beauty of the photos was startling and their unique perspective on the world undeniable. From images that felt like Georgia O'Keeffe paintings—washes of vivid color where a child had placed the camera so close to a flower that it seemed to convey the flower’s own viewpoint—to clouds and sun flare, where a child had pointed the lens straight up at the warm spring sky, each image was vivid and consuming and very clearly not one an adult would ever have captured.

Giving a child a camera is one of the surest and most concrete ways to gain an understanding of their perspective. When children are able to control the lens and the framing, they often reveal a very different world from the one we adults see, articulating stories and understandings visually that they may not yet have the words to express, or that we just haven’t been able to hear.

I was reminded of these preschool photographs this week when I read an article about a project in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, in which children were given cameras to capture their community. As the article notes, the Tenderloin is typically defined in the media by a focus on its harshest realities—the prevalence of homelessness and drugs. But, through their photographs, the children of the Tenderloin tell a very different story. They depict a community full of friendship, play, cultural connection, and, most importantly, a strong sense of home. One child, Khaled, who will begin middle school in a different neighborhood next year, said of his photographs, “This represents [my] childhood.” Another child, Miguel, said, “What people don’t realize is that the Tenderloin is beautiful.” Reema said, “I was with my friends when I took this photo. It made me feel happy and grateful.” And Nsimba said, “The Green Community Park is my life. I like the nice people that works there. I like how they let us take off our shoes and run around the grass. When I’m at the park I see beautiful butterflies, flowers, bees.” These children see joy and belonging where adults only see hardship.

To be clear, children’s perspectives are not always rosier than adults’. As the artwork I included in this essay, depicting children’s feelings about the presence of ICE in their communities, illustrates, children are often trying to tell us that they’re frightened or alone or in hiding or just in need of something radically different from what adults are providing.

The point of viewing the world through a child’s eyes isn’t to reassure ourselves that “the kids are all right.” Rather, the point is simply that the kids have something to say and that their perspective is important, valid, and too often ignored or misunderstood.

Because children’s photographs and drawings often reveal ideas or feelings that they don’t yet have the ability to fully articulate, or that they are afraid to articulate, listening to children is always about more than simply hearing their words. Truly listening to children requires that we observe all the small ways they show us who they are, what they love, and what they need.

I think about the children I’ve had in my classroom over the years who didn’t speak at all for various reasons but still found ways to show those willing to pay close attention what they needed. The child whose silence often came with a tough and defiant glare, but who would also curl up in my lap like an infant craving contact and care, for example. Or the child I wrote about here, whose quiet curiosity became a new form of leadership when a few peers took the time to follow his inquisitive gaze into the trees.

I think about the writer, Sandy Ernest Allen, describing the trans boyhood he never had, because the prevailing message of the adult world around him told him that what he knew wasn’t real, valuable, or permissible. He says of his childhood self,

“I know how much nobody ever listened to him.

I know how much nobody ever told him: I see you exactly as you are.

And: You matter, kid.

And: I hope you stick around.

I’m so grateful to him, that he did.”

I wonder what it might have meant for him to have had the trans preschool teacher I once hired as his own preschool teacher—what it might have meant, not only to be seen, but to have his own internal knowledge gently reflected back by an attentive, healthy, caring adult. I think about this teacher often, too, and how his mere presence was surely a powerful form of listening for some of the children in the class he taught.

I think about the high school history teacher, Jesse MacKinnon, whose students share so much about their own lives and about their understanding of power in his history class. As a teacher myself, the subtext I read throughout his writing is a strong awareness of a classroom where kids know they have the ear of a trustworthy adult and can, as a result, share their most difficult questions and their honest observations. MacKinnon notes,

“They may not recall every detail of a Supreme Court case, but they know what happens when someone speaks and no one listens. They understand who gets believed. They know when kindness is genuine and when it is performative. They read adults as easily as they read each other.”

I think about my own son, who’s been working with his best friend this weekend on a letter to their principal about why removing the advisor they have come to trust— who brought them out of their tentative middle school shells and nurtured their emerging confidence and sense of belonging—feels so much more impactful and significant than their school seems to realize. In the most simple terms, he and his friends felt seen and heard by a caring adult, and they understand how rare and precious that is, and how worth fighting for.

I’ve been lingering on all these myriad ways children of all ages try to tell us who they are, what their lives are like, how they see the world, what matters to them, and what they need, because, in general, we really don’t do a very good job of listening to children or of taking their voices seriously.

We’ve never been great at this to be honest, particularly in the United States. In fact, the US is the only country in the United Nations that has failed to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child, despite having had a strong hand in writing those very rights. The reason for this is fairly straightforward. According to Human Rights Watch, the US consistently fails to meet many of the standards for children’s rights set forth in the Convention.

This is not new. The history of our failure to protect children runs deep. But I do fear that we’re sliding even farther backwards. There is no question that children suffer more when we fail to listen closely and heed their voices, in whatever form they find to communicate with us. And children certainly suffer more when we do not view them as having any inherent rights at all. In truth, we all tend to suffer more, adults and children alike, when we deprioritize children’s needs and stories.

A significant factor in our failure to listen to and protect children is a strong historical tendency in the US to view children through a lens of property rather than personhood. This view of children lurks behind the framework of “parents’ rights,” which is a clever turn of phrase, meant to convey the perception of protecting children. In fact, the adult rights demanded under the umbrella of “parents’ rights” more often put children at significant risk of harm. The “parents’ rights movement” has a long and very dark history, rooted primarily in Christian nationalism and resistance to school desegregation. But it has become an increasingly powerful resurgent force in our age of book bans and restrictions on pediatric medical care, from vaccine refusal and bans on gender affirming care to cancer treatment, not to mention the reemergence of child labor and the imprisonment and abduction of migrant children and their families.

There are two critical fallacies that are essential to understand whenever the phrase “parents’ rights” is used. First, the specific rights this movement fights for purport to be about protecting children from harm but are actually almost always about dominance and are often leveraged to defend some of the cruelest things we do to children—think, for example, of child marriage, factory labor, and children as young as 7 being tried as adults, all of which are allowed in many states. In fact, no state rates above what Human Rights Watch describes as a C grade when it comes to children’s rights.

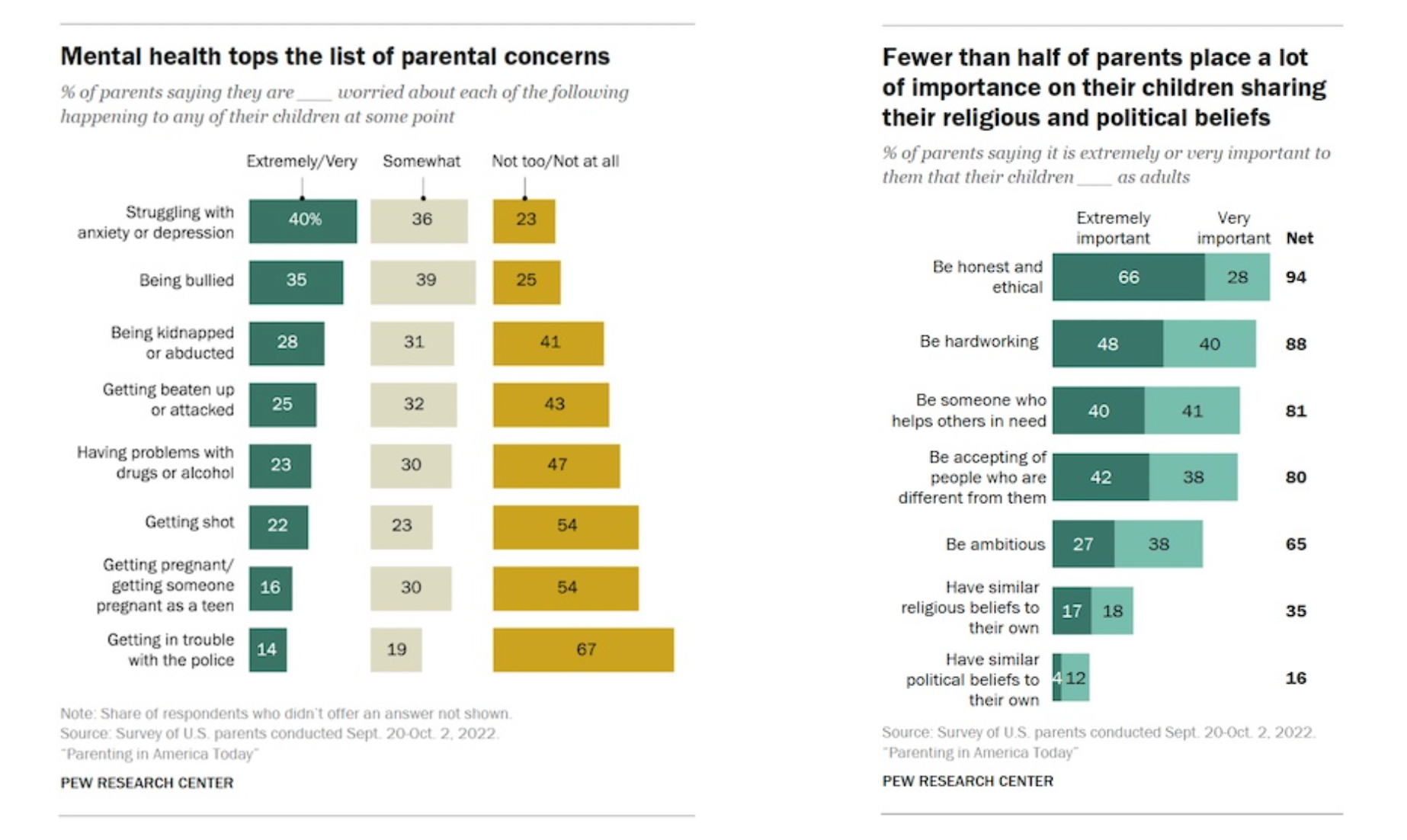

The second fallacy of the “parents’ rights movement” is that most of the policies it advocates for are not actually supported by the majority of parents. Even the policies that grab headlines, as though they are held by many, are not even on the radar of concern for most parents. Statistically, the most recent data from Pew Research indicates that parents’ top concerns are for their children’s mental health and their physical safety from bullying, kidnapping, drugs, and gun violence. According to surveys reported by the National Education Association, 76% of parents trust their child’s school and 74% express a “high degree of confidence” in their child’s school librarian. Further, the vast majority of parents report that their top priorities for their children are for them to grow up to be honest, ethical, hardworking, helpful, and accepting of differences, compared to only a small percentage of parents who prioritize raising children whose religious and political beliefs match their own.

The takeaway here is that most parents want their children to have access to mental healthcare, to be safe from violence, and to grow up to be caring adults. Of course, children need adults to provide for them and, at times, guide them and set boundaries that ensure they are safe, educated, healthy, and nourished. But don’t be fooled. The “parents’ rights movement” is not about whether you can insist your child eat vegetables, hold your hand when crossing the street, or even take them to whatever religious institution you choose or make basic decisions about where they will attend school. This movement is, instead, about enshrining the right of a small number of adults to ignore children’s voices and basic needs, to prevent them from being exposed to any diversity of people or ideas, and, often, to subject them to very direct and obvious harm or abuse. Increasingly, this movement is also about ensuring that other parents have no choice but to raise their children within these extreme and dangerous confines as well, under the guise of “parents’ rights.”

As a parent and as a teacher, I’m responsible for children. I take this responsibility very seriously. Granting children rights doesn’t diminish this responsibility or set an expectation that children should somehow be independent or expected to make choices beyond their developmental capability. The Convention on the Rights of the Child takes the responsibility of adults toward children extremely seriously as well. In fact, many of the most basic rights of children involve their need to be cared for and guided by adults—parents, guardians, institutions, and even the government (such as in the case of healthcare or legal protections). Granting children rights in no way prevents parents from parenting, but it does protect children from harm.

A fundamental characteristic of rights in a free society is that one individual’s rights don’t usurp the rights of another person. The “parents’ rights movement,” on the other hand, seems to argue the opposite—that the rights of adults ought to inherently negate the rights of children. The argument for “parents’ rights” is not about recognizing children’s very real dependence on us; it is about viewing children as property.

As Kristen Weber, the National Center for Youth Law’s senior director of child welfare, says,

“We have this legal historical construct, both in the world of policy and the world of litigation, we have been trying to shed, which is that children are chattel.”

She goes on to note that the “parents’ rights movement” is an indicator that we often still view children as property or as chattel, rather than as individuals with rights. I’ve spent most of my career working with parents, and I truly don’t think this is how most parents want to view their children. The data I cited above about parents' priorities and values underscores this. But we also have to acknowledge that we are all steeped in a history that does view children this way, and that this history permeates our thoughts and actions in ways we may not always realize.

I often end these notes, particularly when they explicitly touch on the way we understand and treat children, with an ask of readers. So my request for you this week is to find some time to read the Convention of the Rights of the Child for yourself. You can read the full text here or a child-friendly version here.

In reading, consider whether granting children any of these rights would really prevent you, in any way, from being a responsible parent or adult presence in a child’s life, as the "parents' rights movement" suggests. Then, I’d ask you to return to where I began this note—the images and voices that give us a window into children’s own beliefs, values, perspectives, joys, and fears. Ask yourself what children are trying to tell us about what they love and about what they need. Ask yourself whether we are really listening. And ask yourself what we are protecting by silencing children or by denying the significance of their voices, whether intentionally or inadvertently, as we elevate the rights of adults.

And, if you need a dose of hope and beauty, might I suggest giving a child in your life a camera? Look closely at how they see their world. Ask them to tell you about it. In my experience, their vision is clear and their perspective powerfully reorienting. Most importantly, in doing so, you will be communicating to a child, in a very concrete way, that you care about what they see, what they know, and what they have to say.

Wishing you the care and courage to look at the world through a child’s eyes,

Alicia

P.S. Don't forget to check out this week's Helpful and Hopeful links below!

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- We are the song death takes it own time singing by Benjamin Riley

A beautiful rumination on what it means to be human, to care for one another, to wring meaning out of suffering, and to find relief in imagination—and how we conceptualize all of this in the context of AI. - The Story of Overcoming Hunger One Poem at a Time

- "The tree is trying its best" (same, tree, same)

- Meet the Man Behind Baltimore's Free Book Movement

- We can tell a different story about Hurricane Katrina and who we are in disasters by Rebecca Solnit