“We’re not cold. We’re not afraid.”

Lessons in heartbreak and in holding each other up

“We hold these truths to be self-evident…

We’re the cure for hatred caused by despair. We’re the good morning of a bus driver who remembers our name, the tattooed man who gives up his seat on the subway. We’re every door held open with a smile when we look into each other’s eyes the way we behold the moon. We’re the moon. We’re the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you.”

~Richard Blanco,“Declaration of Interdependence”

I hope you’ll forgive me for lingering on Minnesota over the past few weeks. I know I’ve been dwelling here. But, as the news is beginning to break through into bigger and more unambiguous national headlines, I trust it’s becoming clearer why, beyond my personal connections to the midwest, the events unfolding there are worthy of an extended and unflinching gaze.

So much in recent weeks has been especially horrific, but the response of ordinary people has also been extraordinary, inspiring, and instructive. We should never need devastating events, documented and broadcast widely, to crystalize public understanding of a dire situation, though more often than not it does seem to take tragedy to rouse us from caution, equivocation, or simply lack of awareness. But grief and anger at how we reached this point should not negate or obscure the significance of the courage and care being enacted now by so many regular people and their communities.

Sometimes it’s only through heartbreak that our compassion is ignited powerfully enough to move us beyond fear, denial, or apathy. In addition to Richard Blanco’s reminder above about our interdependence, which echoes in my ear often, I’ve also been hearing Stanley Kunitz’s words about heartbreak in my mind all week,

“In a murderous time

the heart breaks and breaks

and lives by breaking.”

Proximity to grief and human frailty plays an unavoidable role in our ability to recognize the need for courage and care, and to act upon that recognition. Our hearts live by breaking.

As people have tried to understand why Minnesota has become such a strong model of community care during these very frightening weeks, a refrain I’ve heard multiple times has been a connection between the harsh cold of Minnesota winters and the strength of community support that this fosters, even in the most normal times. Though it’s surely not the only factor, I think it’s fair to say that there is something about living in a place where the weather routinely keeps people in touch with their own mortality that breeds a uniquely sturdy and practical form of interdependence.

My grandfather, a Minnesota high school biology teacher, used to tell a story about being caught in the 1940 Armistice Day Blizzard in Minnesota—the most deadly snowstorm in the state’s history. He and his best friend were caught in the storm together and made their way home through blinding, frigid conditions that many others didn't survive. They walked backwards at times because the wind was so strong it would knock them off their feet and into the ditch if they tried to walk forward. He recalled it taking them about nine hours to travel the ten to twelve miles home together on foot. They were fifteen years old. He attributed their survival that day mainly to the fact that they were both wearing hip boots. In addition to this very practical protection, though, I also can’t help but think about how things might have gone differently if either he or his friend had been alone. We are often braver and more able to stretch our endurance when we know someone else is counting on us, so it feels significant that they were counting on each other, especially at fifteen.

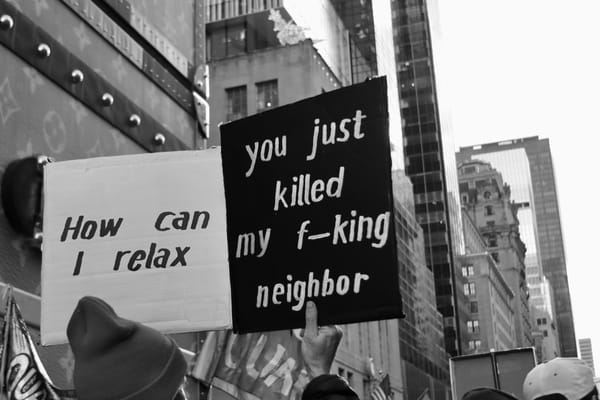

It seems both poetic and mobilizing that snow and freezing temperatures spread across much of the country this weekend, along with the inspiration of courage and mutual caretaking occurring in Minnesota, as if these lessons were carried by the wind itself. In Boston last night, crowds stood in twelve degree weather chanting, “We’re not cold, we’re not afraid, Minnesota taught us to be brave!” The ordinary bravery inspired by the images of so many regular people—teachers, local shop owners, nurses, retirees—all undeterred by the intimidating power of nature, let alone the weapons trained on them, is surely part of what is making the response in Minnesota feel contagious.

But, in addition to the refutation of the cold, I think the repetition of “we” and “us” in that chant is also critical. As powerful as self-interest and self-protection can be, protecting those we love and feel responsible for can stir a different level of fortitude; acting for others allows us to step over the instinctual fear and caution sparked by concern for our own safety, propelled instead by a drive that feels bigger than our own fate.

With this in mind, it’s also been strikingly clear this week that connecting with others at a hyper-local level and building community among neighbors really does matter. These intimate relationships motivate us to do more than we might otherwise do, and they create practical infrastructure to draw upon when individual resources are insufficient.

A recent paper from the neuroscientist M.J. Crockett describes the notion of “thick empathy.” Crockett defines this as empathy that is rooted in both personal understanding of the situation someone else is facing and deep knowledge of the person themselves. They note that “thin empathy”—empathy that does not have this robust personal knowledge to support it—is also remarkable and important. In the conclusion of the paper, they explain, “Isn’t it incredible how much we can connect with one another, on the basis of so little access to others’ inner worlds?” It is this capacity to connect across difference and across gaps in interpersonal knowledge, Crockett suggests, that establishes the foundation for the development of thick empathy, moving us toward deeper and more robust bonds of understanding and care.

As I’ve written previously, I’ve seen this trajectory—empathy transforming and deepening through shared experiences and increasing personal knowledge—among preschool children in the classroom. Despite the fact that children are often viewed as egocentric, the ability to care deeply about one another is not exclusive to adults. Children’s early interest in playing with peers, even those they may not know well or at all at first, simply because it’s fun to play together, grows into deeper relationships over time. As children play together, they develop relationships that are rooted, not only in initial common interests, but in knowing and understanding one another with increasing clarity, specificity, and depth. As their shared experiences establish relational tissue, even very young children become more and more invested in each other, not only in the activity of play for its own sake. I saw this manifest in a shift from repairing harm when it inevitably occurred to actively striving to prevent harm. As they played together, the children constructed shared experiences and specific personal knowledge, and in turn they became much more proactively committed to mutual wellbeing.

I suspect that what we are witnessing now, both within and beyond Minnesota, is at least in part fueled by a similar transformation—an ever-deepening development of thicker and thicker empathy, supported by the experiences that community ties create. Anchored in the shared but relatively general experiences of local culture, pride, and, yes, cold temperatures, connections are strengthened through the many more micro, personal shared experiences of daily neighbor-to-neighbor interaction: school life, Parent-Teacher Associations, sports team practices, repeated run-ins at favorite local shops, and a million other mundane examples. Through these interactions, strangers become known fixtures in our lives, and we become invested in one another in ways we often don’t realize until those bonds are tested. But when they are tested, if they prove strong enough—or thick enough, to borrow Crockett's term—the shared experience of struggling, celebrating, and just living each day together becomes something more. Caring for each other through adversity surely fosters one of the most thickening and emboldening experiences of community connection and solidarity. I don’t think it is a coincidence that many of the organizational touch points, as risks have escalated in Minnesota, have been local schools, restaurants, and beloved neighborhood shops. These are the spaces where community connections spark in ordinary times, so it seems natural that they would become the hubs of community defense. They are the vessels of shared experience and mutual knowledge.

In the classroom, young children move from noticing tears and repairing harm after it’s occurred to anticipating and defending against harm in advance the more connected they become and the more shared experiences they establish. Though we adults probably have many more distractions and obligations in the course of a day, acting as barriers to getting to know one another the way children do through the consuming nature of their play, our connections have the potential to form similar relational and experiential webs over time, shifting us from reactive to proactive care.

As others have explored in much greater depth and detail, an unusually robust history of solidarity across difference has also contributed to Minnesota becoming a heated target, and to the community response. The relationships that have developed in local communities there, deepening interpersonal knowledge and experience and organizing capacity across difference, have surely undergirded the empathetic bonds we are now seeing on display. Perhaps even more importantly, there is much we are not seeing, because a great deal of the community support that is happening is not the bold gestures making the news, but the quiet networks of grocery deliveries, community alert texts, laundry, and child care happening in the background and making the bolder, more public work possible. These quieter networks are surely where community relationships, established over time through regular daily life, prior to this moment, are most significant.

As one small personal example, this weekend my cousin and her husband raised $2,000 and collected over 530 pounds of food in 48 hours for a local Minnesota food pantry, through their cozy community yarn shop. They were able to do this, I’m sure, because they are more than a storefront. They are a hub of connection, running classes and knitting circles that link people to each other in ordinary, relational ways. The mutual knowledge, trust, and commitment that these interactions establish leads people to show up to support each other and their neighbors in more vital ways when the call goes out. The parallel between adults knitting side-by-side, and then transforming those quiet connections into more active solidarity, and my preschool children befriending each other in the block area, and then looking out for each other on the playground, feels very direct.

And, perhaps most importantly, witnessing the way these kinds of familiar, highly relatable, local, community connections are morphing into vital support networks, as life has become dangerous, appears to be causing a contagion of parallel solidarity and social networking across a widening geographic range. Communities all over the country seem increasingly primed to activate their own networks of care.

I read this mantra from an organizer in Minnesota yesterday: “We can’t always take away the hurt, but we can take away the alone.” On a very basic level, that has to be the most essential quality to focus on and spread widely. As I wrote last week, this is a crucial lessons we can offer to children when they are scared, and it is probably the most important lesson for all of us, adults and children alike. We can’t wash away the pain of generations of fear and trauma for those who have always been targets of violence, and we can’t eliminate the pain and fear of the current moment. But we can “take away the alone,” and there’s a surprising amount of power in that.

It is not insignificant that Alex Pretti’s last words were, “Are you okay?,” spoken to a woman nearby, as he tried to help her. It seems clear from all the details of his life that have surfaced that these words were emblematic of who he was as an individual. But they also seem to be emblematic of the fabric of defiant care that’s emerging across Minnesota and beyond. If there is one thing to carry forward from this most recent heartbreak and from all the fear, I hope it is those words: "Are you okay?" They should be on the tip of all of our tongues as we hold each other up and carry each other forward. I hope these words are reflective of the language and the lessons that children are learning, even in their own fear, as they watch their communities rise up in support of one another. And I hope they are the words that define what we build next.

“We’re the promise of one people, one breath declaring to one another: I see you. I need you. I am you.”

Wishing you care and courage,

Alicia

P.S. Before you go, take a few minutes to listen to Minnesota Poet, Robert Arnold.

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- Read This If You're New and Trying to Find Your Way, Mariame Kaba

- Hundreds of Clergy Descend on Minneapolis, Jack Jenkins

- Your Friendly Neighborhood Resistance, Kerry Howley

- Restaurants Become Hubs of Solidarity, Em Cassel

- Protest Breaks Out at Dilley Immigration Detention Facility Holding 5-Year-Old Liam Ramos, David Martin Davies

- Resources for Supporting Minnesota