What Children Know about Power

And why we should stop comparing tyrants to children

“And Max the king of all wild things was lonely and wanted to be where someone loved him best of all.

Then all around from far away across the world he smelled good things to eat so he gave up being king of where the wild things are.

But the wild things cried, ‘Oh please don’t go—we’ll eat you up—we love you so!’ And Max said, ‘No!’”

~Maurice Sendak, “Where the Wild Things Are”

When adults act in deeply self-centered ways, when they behave irrationally, or when they attempt to exert indiscriminate dominance, we often have a reflexive instinct to compare them to children. There’s a certain utilitarian value to this, because comparing an adult who aims to appear powerful to a child is instantly diminishing, particularly in a cultural context that consistently devalues actual children. Referring to an adult as a child can be a quick way of reminding people that the symbols or authority are usually more fragile than they seem, that holding a powerful position is not itself evidence of maturity, intelligence, or worthy intentions, and that such power is often weaker and more vulnerable than it appears.

These are all important points to communicate, especially as we face a rapid and frightening rise in authoritarianism. Ridicule and humor are also effective and often essential tactics in exposing and leveraging the weaknesses of those who seek to convince us to submit to extreme power. Humor is often the quickest way to reveal that the emperor has no clothes. But I’d like to suggest that comparing the chaotic and callous actions of adults—particularly adults in positions that actually do grant them substantial power—to the behaviors and motives of children misrepresents both childhood and the true dangers of extreme authority. There are many avenues to revealing cracks in power. In fact, children are often experts at doing just that. Perhaps we can even learn from children as we practice resistance. But, whatever tactics we choose, let’s move away from making childhood a metaphor for the worst adult impulses.

The features of adult behavior that most often elicit comparisons to children are a lack of emotional control, the use of exaggerated symbols of authority that create an impression of pretend play, and selfishness. We saw all three of these features on display in a very public way this weekend, as an outlandishly expensive military parade rolled through the streets of Washington D.C. It was a lavish use of resources and theatricality, designed to buttress the ego of one of the most powerful people in the world, as he observed with seeming boredom and irritation.

Having organized and attended many children’s birthday parties in the course of parenting and teaching, it is certainly easy to overlay these farcical features onto a child’s birthday party, complete with costumes and a few tantrums. But here’s the problem. Children don’t have much real power. And adults do. Certainly, the commander of the third largest military in the world, and arguably the most powerful, wields very real might, whether we are comfortable acknowledging it or not. In this most basic but significant way, he is not a child. No adult is.

The fact that a military parade in the capital was so sparsely attended, particularly as massive opposition protests surged around the rest of the nation, is surely a sign of political weakness. The comparative crowd size images provide a striking visual indicator of popular sentiment. It is undoubtedly important strategically and perceptually, when confronting the threats of real dominance, to observe and communicate the signs of its vulnerability. It is simultaneously important to remember that, as we’ve seen in the streets of LA over the past week, there is nothing meek or childlike about any armed force. Even a weak regime has tremendously dangerous tools at its disposal. As the historian Thomas Zimmer explains in an English language summary of an article he published in German today,

“Two things are true at the same time: The regime is encountering a lot more resistance than they know how to handle, they are vulnerable. Yet they are also dangerous, controlling the coercive powers of the state, fueled by a paranoid, conspiratorial siege mentality that pushes them to escalate.”

I hope it is obvious at this point that children, even in their wildest moments of rebelliousness or emotional dysregulation, possess none of this power. The ridiculousness of the comparison is, of course, what lends the parallel its satirical value and humor. But, in comparing powerful leaders with armed forces at their fingertips to children, we also convey a degree of harmlessness that is a precarious fiction. And, while children don’t have the ability to wield real authority, I also think the quickness with which we’re amused by comparing the feckless actions of those with true power to children is a reflection of our adult tendency to minimize the real depth and complexity of childhood. This is where I think the comparison between children and would-be rulers becomes particularly faulty and fraught.

Several important features of childhood are critical to understand here. First, while children are more limited in their ability to regulate their emotions, and this can manifest in dramatic outbursts at times, they don’t actually relish this loss of control. Where powerful adults often leverage their own rage as a tool for instilling fear in others, children are usually frightened by their own emotions in the moments when they lose control, and they're typically relieved by the coregulating capacity a calm adult can offer to support them in regaining stability.

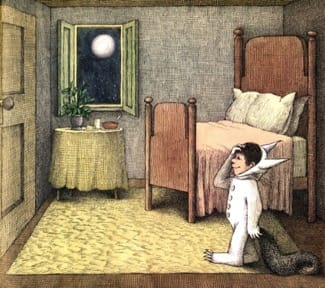

As an example, the rage that Max famously displays “the night he wore his wolf suit,” in the opening pages of Where the Wild Things Are, is very true to the vehemence of children’s emotions, just as his retreat into the fantasy of ruling over an island of monsters is very true to the way children use fantasy to explore and express their most overwhelming feelings. But, ultimately, the desire for comfort, connection, and safety that Max experiences at the end of the book, once he’s exhausted this exploration and decided to relinquish his crown and return home, is also very representative of the way children resolve their biggest feelings—not by holding fast to a powerful role, but by releasing that character and returning to the stabilizing force of their most secure bonds. In my experience as a parent and a teacher, children almost always seek out comfort and connection after a tantrum has resolved, not further power struggle. Unlike adults with real power and a true desire to rule, children don’t usually aim to extend their own rage, to leverage it against others, or to hold fast to power. Their play is a vehicle for understanding and expressing emotions and testing the limits of their developing skills, but stability and connection are always parallel drives that they return to again and again.

Max waves goodbye to the Wild Things and returns "to the night of his very own room"

The way in which children utilize play as a vector toward, not away from, regulating their emotions is related to a second important distinction between children and powerful adult figures, who use theatrical displays as a means of control. Children’s play is fundamentally an expression of curiosity more than of any other goal. When adults use symbolic gestures to signify their authority, they are usually attempting to make their own power more robust and rigid—to freeze their rule in the visual signals of crowns, opulence, or emblems of force. Though it’s true that children are often drawn to exploring power in their play by taking on the characters they see as authoritative, whether in the form of a parent, a superhero, or even a king, they primarily engage in these enactments as a way of asking and investigating questions about structures of power not as a way to wield power or inflict harm.

This is evidenced by the way children assign and move between play roles. Most children are just as likely to take on the role of a kitten or a baby as they are a superhero or a ruler, and, in the course of play, children will often reassign parts and trade roles. This is because the fundamental goal of play for children is learning, and taking on the experiences of a range of characters is part of that learning process. They observe a wide variety of roles in the world around them, and they try those roles on through play—just as an actor does—in order to better understand the workings of human relationships. Children’s play is deeply exploratory and as such it is fundamentally empathetic, not coercive.

At times, children do use fantasy play to bolster their sense of security. Taking on the signifiers of a role that conveys power or courage, especially when they are feeling particularly small and vulnerable, can be protective and emboldening for children. I remember vividly a period when my family was going through a frightening time, and my son, who was three, would periodically mimic the deep voice of his favorite heroic cartoon character, “Fireman Sam,” when he needed to feel more grounded and brave. Imagination is powerful. But, even in these moments, children generally use performative roles to explore a range of emotions and experiences and to bolster their sense of safety, not to instill fear in others. And they typically relinquish these roles, just as Max did, once they are feeling safer and more confident.

This is directly connected to a third important, distinguishing feature of childhood. Children generally know their enactments of power are not real. As convincing as their play can be, and despite their tendency toward magical thinking, children do understand the basic symbolic nature of their play; most children know that they are not really Superman or Princess Elsa, even as they immerse themselves deeply in these roles. Research has shown that even children who convincingly describe and interact with imaginary friends know that these characters are fantasies and will express concern for adults who seem to take their imaginary friends too literally. Psychologist and researcher, Tracey Gleason, describes children’s fantasy play as occurring within a bubble they know exists but choose not to pop. Children intentionally use symbolism to engage with, explore, and process their experiences. This is very distinct from the use of symbolism by powerful adults to exert emotional leverage and inspire awe or fear.

Finally, there is a difference between developmental egocentrism and selfishness, and this is essential to differentiating behavior that is actually childish from behavior that is callous. Selfishness is, perhaps, the trait that most commonly triggers a labeling of adult behavior as childish, and it is also the comparison I find most problematic in both its inherent disparagement of childhood and its fallacy. It is true that children have difficulty taking the cognitive perspectives of others. This is what is meant when children are referred to as egocentric. But, as I’ve written before, the cognitive capacity for perspective taking is distinct from emotional attunement, and, with regard to emotion, children are deeply empathetic. They feel the emotions of others from birth and begin attempting to help one another in early toddlerhood.

Additionally, children are increasingly able to understand other people’s thoughts and experiences on a cognitive level over time precisely because they are highly curious and driven to make sense of other people. Much of children’s play and daily engagement with both peers and adults centers around their active effort to decipher and understand how others think and feel. The difficulty children experience in perspective taking is one they are constantly trying to untangle and overcome. This drive to understand others runs directly counter to a selfish orientation.

To describe a child as selfish because they are not yet fully able to understand other people is akin to describing an infant as lazy because they are not yet able to walk independently or as uninterested in communication because they are not yet fluent speakers. In fact, the opposite is true for all of these examples. Children are deeply motivated to learn and to develop skills they don’t yet possess, including to better understand a diverse array of people. As the researcher, Alison Gopnik explains, “Babies and young children are like the research and development division of the human species.” Curiosity about people other than yourself is the trait that most powerfully defies selfishness, and it is also a trait that is often lacking in adults who seek to exert power and dominance over others. Spend just a few minutes watching the intensity with which a baby gazes at, mimics, and attempts to solicit connection, engagement, and communication with a caregiver in the earliest months of life, and it becomes very difficult to view children as selfish or self-focused.

I suspect that one of the most basic reasons we are drawn to identify the behaviors we find problematic in adults as childish is because this allows us to separate ourselves from that behavior. We elevate our own sense of maturity by relegating the qualities we find distasteful to the distant realm of our own childhood. But I think our understanding of both children and of the extreme power dynamics that can develop among adults would be better served by looking for other explanations and representations.

Children surely lack many fully developed skills and understandings. But they are constantly striving to learn and to connect, and this makes them radically different from adults who aim to control and dominate. As tempting as it may be to imagine those who seek to rule us as impotent, impetuous children, let’s catch ourselves when we stumble into these comparisons. Let’s try to find new metaphors—better metaphors. And let’s look to childhood, not as a symbol of our most base instincts, but rather as a source of inspiration for our own adult curiosity, compassion, playful ingenuity, and even our own rebelliousness.

Wishing you playfulness and care,

Alicia

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- We are no longer free, but we can win our freedom back

- Non-violent protests are accelerating

- "We carry the radiant future: a reckoning, a promise, a song. This weight, this love, was never a burden."

- How to advocate for trans rights in your community

If you think someone else in your life might need some hope, please share! It’s always easier to hold onto hope when we’re not doing it alone.

And if you appreciated this post and are not already a subscriber, please consider subscribing to Notes on Hope.