What We’ll Build Next

Now is the time to embrace imagination

“But I believe there are birds

whose songs of love aren’t heard

by people who need to care.”

~ From a child’s letter to ICE

Valley View Elementary School, MN

I spent several years as the director of a preschool that followed the Reggio Emilia philosophy of early childhood education. For those not immersed in education terminology, this is an approach to young children’s learning that places a high degree of significance on their imagination, on their many forms of expression—what Reggio teachers term “the hundred languages of children”— and on their capacity for building meaningful understandings, even in their earliest years. Importantly, it is also an approach to education that emerged out of the literal rubble of WWII, as the people of a city in northern Italy asked each other what future they wanted to build from the dust and ashes of war. Instead of simply rebuilding what had been, the people in this city envisioned an entirely new way of living that was rooted in centering the experiences and discoveries of the youngest members of their community. Just barely free from the grips of Fascism, they imagined, "a new form of education that would ensure against future generations being brought up in toleration of injustice and inequality."

Citizens of Reggio Emilia, Italy rebuilding from the rubble of WWII

The construction of the first Reggio school was paid for by the sale of a tank, three trucks, and six war horses. And with that, the people traded destruction and oppression for the building blocks of a new, more hopeful vision—one that not only spoke abstractly of children as the future but actually constructed a reality in which children’s needs, rights, and growth were the guiding principles of society. Loris Malaguzzi, whose vision for education shaped the Reggio Emilia approach, once said,

“Observe and listen to children, because when they ask, ‘why?’ they are not simply asking for the answer from you. They are requesting the courage to find a collection of possible answers.”

This was not only a statement on how teachers ought to approach children’s curiosity, but also a powerful reminder to adults that we have much to learn from the inquisitiveness and wide-open imagination of young children. Malaguzzi viewed education as a buttress against the Fascism he had endured and a path to a better, freer future for the next generation. A society that truly respects children and believes in them, not only as vessels of future potential or pawns in political ambition, but as full human beings with valuable ideas in the here and now, does not merely become more humane in its treatment of children; it also opens itself up to a reality in which there are always many possibilities available—more than we might have otherwise envisioned for all of us, adults and children alike, and certainly many more than were ever possible under the oppression that Malaguzzi and the people of Reggio Emilia had so recently been liberated from.

A critical feature of Malaguzzi’s vision, which made this expansive way of seeing both children and the reconstruction of society so powerful, was that his conception of education was not one that centered itself on protecting children from the world around them, as dark as it was at the time, or on controlling, constraining, and defining their reality. Control is so often the educational framework we are given by those who claim to be putting children first but are actually only seeking to ensure that children’s lives serve their own visions of power. Malaguzzi, however, had seen the dangers of such control first hand. Instead, he asked those responsible for the care and learning of children to open the world up to them and then to pay very close attention to their questions, their hypotheses, and their imaginations—to not only teach children but to learn from them and with them. His view of learning and of children's rights was not just an educational philosophy but a claim to freedom of thought and expression, anchored in respect for the youngest wondering minds.

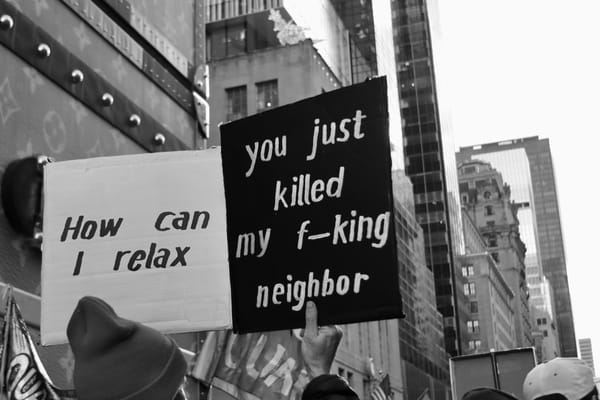

Those who tell you they want to protect children, but then present a vision of childhood that involves narrowing the scope of children’s experience to a tightly prescribed tunnel or restricting the right to even have what most of us would consider a childhood to the fortunate few, are not really interested in caring for children. Visions of childhood that are so constricted they can only serve to replicate what already exits are too often the same visions that have led to the tanks and the piles of rubble in the first place.

Malaguzzi, by contrast, looked to children and asked what they might have to say about the world and how their thinking might open us up to ideas that adults alone could never have imagined. What if, instead of seeking to funnel children into a predetermined adult reality, defined by power, and limiting their world to a doll’s house version of that very reality, we threw open the doors for them to explore and opened ourselves to the possibilities of what they might find and build for themselves? What if we cared for children by walking alongside them and exploring with them? What might a world that truly welcomes children’s exploration and expression look like? How might that world be different for all of us? Could a world that organizes itself around the discoveries of children in fact be gentler, freer, and more expansive for everyone? These are the questions that a small city posed, as they endeavored to build a new world from the bits and pieces of the old one, now shattered—beginning with a school.

It is significant that Malaguzzi and the people of Reggio Emilia envisioned this new reality for their children as they were surrounded by the rubble of a war that stole the future from so many children. And it is significant that their first act in bringing this vision to life was to dispose of the tools of war. It may have been because these were the only items of value they had left to barter. But it is powerful, nonetheless, this exchange of weapons for bricks and pencils.

It is often in the darkest moments, when we find ourselves overwhelmed by destruction, that we have the opportunity to imagine something better. We should not have to “burn it all down” to create more inspired versions of the world. Embracing a mentality of unavoidable harm, even amidst systems and structures that desperately need reimagining, is no different from embracing the mentality of those inflicting cruelty now. Inflicting pain, particularly on the most vulnerable, should never be the path toward achieving the changes that we seek, no matter our goals. But, once we are covered in darkness and ashes that we did not wish for, we have a responsibility to resist the cruelty of the present and to contemplate what we might do with all the broken shards. This, I think, is the most powerful lesson that Malaguzzi and the people of Reggio Emilia have to offer us today. As we face our own moment of darkness and destruction, their choice to begin again with children at the center is a reminder that we, too, have choices to make about the future, even as we grapple with the losses of the present.

Reggio Emilia children of the past and present

Children are not only suffering today because they are caught in the crossfire of violence, but because they are increasingly the targets of that violence. It is worth remembering that the current situation in Minnesota began with accusations against daycares and continues to fixate upon and stalk children in child care centers and schools. Whether terrorizing families and teachers in school parking lots, detaining preschoolers, or teargassing families, children are not merely bystanders on the periphery right now. They are prey being actively hunted. It is also worth remembering that the path we are currently on began with restrictions on which books children could read and on the content of their classrooms, under the guise of protecting them. The ruse of that guise should now be very clear. But it should also be clear that unraveling all these harms will have to begin with a focus on children as well—on what a different future for them could look like and on what centering their needs, their voices, and their rights would actually entail. To this day, the Reggio school system describes itself as, "an international centre for the defense and promotion of children's rights and potentials."

Just as the destruction of WWII prompted the people of Reggio Emilia to ask how they would create a better world for their children, out of the darkness of oppression and violence, and in turn how they would build a better world for their entire community, we will have to ask these same questions. And, surely, it is better to begin asking these questions and imagining their answers now than to wait until all of the harm has run its course. There is no self-fulfilling endpoint to cruelty, and envisioning a brighter, freer future usually offers the best motivation to fight for its creation and to do all we can to limit the harm of the present. Won’t we strive even more ardently to care for each other today if we can conceive of a time when we might be able to build something beautiful together? As Malaguzzi said,

“We should think that we have more need of being nostalgic, not so much about the past but more nostalgic about the future. The children expect us in the future where our nostalgia now sees them, and I wish we will all be there.”

If we are sincerely committed to limiting the harm that is inflicted upon children today and ultimately to building a better world for them, we ought to begin, in the spirit of the people of Reggio Emilia, with the desires and visions of children themselves—to open our own lens of possibility to children’s voices and ideas and the multiplicity of worlds their imaginations create every day. We will also have to consider what tools of violence and destruction we will give up to make this vision a reality. What tanks and war horses will we rid ourselves of to build new schools and new town squares out of today’s brokenness?

We don’t have to find the same answers that a city in Italy found in 1945. But I think we do need to begin by asking the same questions about what we hope the world we’ll build next might look like. And, in searching for answers, we would be wise to listen to children.

(Note: Liam Conejo Ramos has been returned home since this video was made, but all of the other data points cited remain true.)

Wishing you the courage and vision to begin imagining tomorrow, even amidst the sharp edges of today,

Alicia

P.S. I don't often post New York Times links these days, because I've found their coverage increasingly meek and complicit in a time that begs for truth and courage. But I'm making an exception for this video, because these children's voices are so important. To learn more about the many other kids like Liam, this is a good resource.

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- The Anti-Ice Movement Is a Caregiving Movement

- Fifteen Below Zero

- I would like this to be on the record as well

- More on "nostalgia for the future," if your curious

- Rent relief for those who can't leave their homes to work is one of the most urgent needs in MN right now. Go to Stand with Minnesota and scroll to "Rent Relief Funds" under "Mutual Aid" for ways to help.

- And don't forget about cookies!