When Children Know We Can’t Protect Them

Listening to Minnesota’s youngest voices

“...we stop at the corner I run my fingers

over her ponytail like it’s my own hair.

She says there’s a cloud in the sky

that looks like a heart but I can’t see

what she sees. I am a mother

so when she is hungry I feed her

and when she asks me how to spell wolves

I explain how some nouns transform

in the plural. Man is men and tooth is teeth

and person who is murdered becomes people.”

~hannah eve levy

In moments of crisis—well, always really, but especially in moments of crisis—my ears, as a teacher and a parent, are perked to the anecdotal breadcrumbs that offer clues about what children are thinking and feeling, and how they are making sense of the most incomprehensible realities. Children don’t have the platforms adults do to amplify their own voices, and articulating their mental and emotional processing, especially for young children, is sometimes murky business. So little snippets of their play and playground chatter are often all we have to gain a window into their understanding.

Over the past several weeks, a theme I’ve been hearing in these bits and pieces of reports from teachers and parents and caregivers in Minnesota is that kids have both a true understanding of the risks they are facing and a strong desire to protect each other. I’m sure it isn’t a coincidence that this perspective among children mirrors the care and courage many adults in Minnesota have been showing. They have powerful models of community care and courage. I’m sure it is also reflective of the fact that, while schools have been a target in every state that has faced surges in ICE presence, for Minnesota the focus on child care and on schools has been particularly intense, beginning with the accusations against Somali-run daycares and escalating with raids at school dismissals and chemical weapon deployment against children, teachers, parents, and even a six-month-old baby.

Children have not only been bystanders and collateral victims of these raids. Along with those who care for them, children have been a primary focus of the violence and fear. No matter how fiercely adults try to protect them, there is no way for children not to feel the heat of weapons that are trained directly on them.

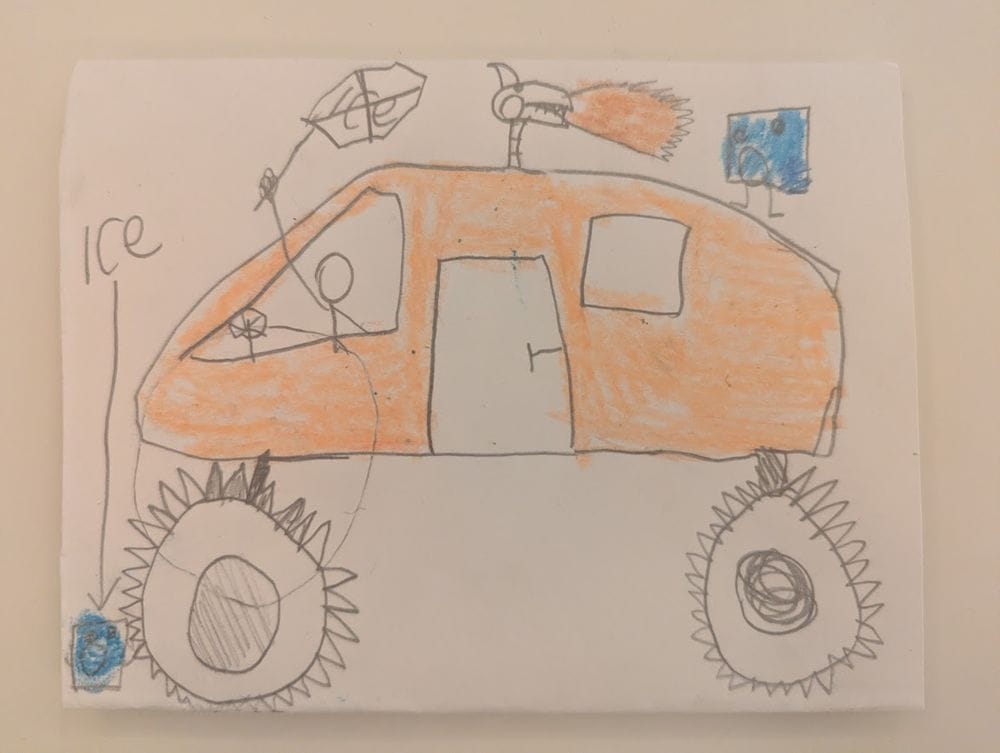

Often, when children are processing frightening experiences, we see their attempts to understand the world around them, and their own role in that world, through their play. I’m sure this is happening in Minnesota living rooms and on playgrounds, just as it has in other places, where very young children have been overheard teaching their dolls and stuffed toys how to stay safe. But, in Minnesota, I am also hearing about children making plans to protect each other in real time, not just through their play but also through what feels much more like direct action. They are not only reenacting events in order to understand and come to terms with them, nor are they using play to rehearse for threats they might face. Children know they are in the trenches and are responding to the moment with an urgency that doesn’t seem to be filtered entirely through the lens of play.

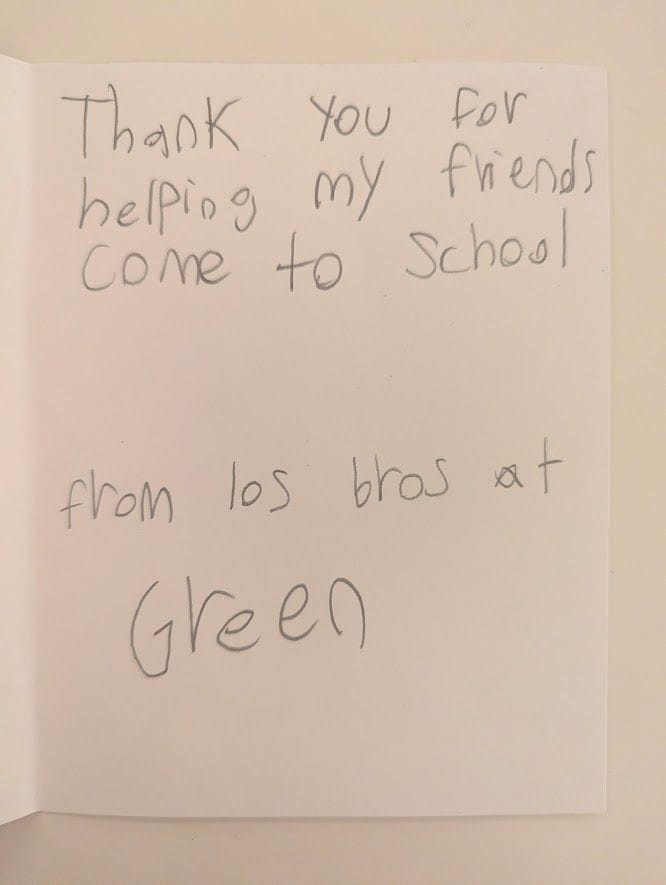

Instead of building snowmen on the playground, fourth graders in Minnesota spent a week building walls of snow to defend their classmates. High school journalists are documenting ICE raids and kids are organizing school walk-outs, in spite of the fact that leaving the literal legal sanctuary space of school property right now is not only an act of protest but of significant risk. I’ve seen thank you notes from young children to the volunteers helping them travel safely to and from school. Kids are helping to pack the grocery bags their parents will deliver to neighbors in hiding, adding gummy worms and oreos for their friends. And a family member, who is a therapist in Minnesota, told me this week that children have been talking to her about how they hope they will be able to protect their friends when ICE comes to their school.

Thank you cards from children to volunteers for escorting them to school during ICE raids in MN, shared on Bluesky

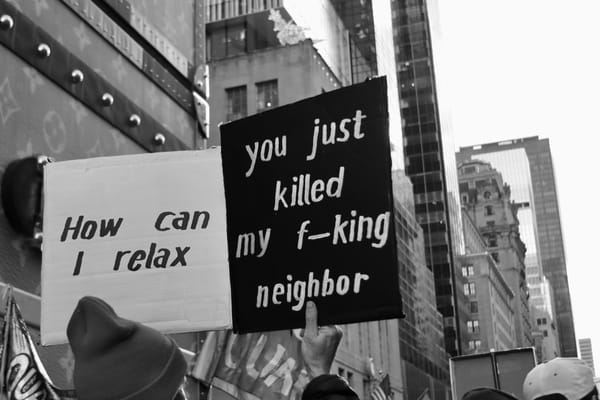

As is often the case when we listen to children’s voices during moments of acute fear, these stories feel simultaneously heartbreaking, unacceptable, and profoundly inspiring. Children should not have to lead us through terror. And yet they often do. The recent escalation in Minnesota has been especially massive and overwhelming. There are currently 3,000 ICE agents in the state, and this weekend the White House threatened to deploy more than 1,500 military paratroopers as well. The targeted terrorization of children is not new to vulnerable communities in the United States. Whether the impetus is racism, antisemitism, islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia, or even domestic abuse, children are often at the vortex of violence and aggression.

It can be tempting, when children are rightly afraid, to try to reassure them by explaining that the adults will protect them, lifting the burden of safety off of their small shoulders. And we ought to be able to do this. In a society that truly values and protects children, we would be able to make this promise. But children are also extremely adept at discerning when our adult words ring hollow. When their schools are under attack and their friends’ parents are disappearing, it is impossible for even the youngest child to fail to see the reality, which is that sometimes even their most trusted caregivers cannot protect them.

This is an extremely difficult truth to hold. As a teacher and a parent, I’m viscerally aware of the instinctive lengths I would go to in order to shield my own child or the children in my care from harm. I’ve written previously about the deep commitment most teachers have to protecting kids in a world in which putting our bodies on the line for their safety is never far from mind in day-to-day classroom life. It feels like a personal failure when we know that, as adults, we might not be able to succeed at protecting children—and it certainly is a social and political failure that we can’t.

Nonetheless, here we are. So, what are those of us who care for children to do when we know—and they know—that we may not be able to keep them safe, because some of the most powerful people in the world don’t see their young lives as worthy or valuable, and whose rage and greed is fixated on their small bodies, on their families, and on their schools. There are no good answers. But I think there are some important, if difficult, lessons.

First, children deserve the respect of our honesty, even when it is heartrending to tell the truth. As tempting as it is to tell them that everything will be okay and that we will keep them safe, sometimes this is more unnerving to hear when it is clearly not entirely true. However, it is true that we will try, and I think this is something we can say to children with the full sincerity of all the love and fear in our own hearts. We can say that we will do everything possible to try to keep them safe, and we can remind them of all the other people in their lives and communities who will also try, with all they have, to protect them. Children know what it is to try. They strive mightily at so many things every day, just to learn and grow. Children know that they are fallible and so are we. But they also know that doing all we can with all our hearts is significant and meaningful. There is a measure of comfort in this, and there is surely comfort in being able to trust that adults are being honest, even when it’s hard, because this is how children know that they are not alone in what they see and feel.

In addition to being honest in what we say to children about the limits of our power, we can also create space for children to be honest with us about their own muddled feelings of fear and courage. As Autumn Brown describes of her own experience parenting through the present crisis in Minnesota,

“I’m having to speak really, really frankly with my kids, both about what is happening, about my risk assessment, about my assessment of their risk level, and then be in daily conversation with them about how they’re assessing their own risk level on a day-to-day basis, which changes each day, right? And making sure that they feel that they’re at choice in terms of where they want to go and when.”

Of course, the words we use for these conversations and the weight of the choices will vary depending on the age and vulnerability of the child. Older children may need to feel they have more agency in the actual decision making, whereas younger children may need us to listen very closely to the tenor and intensity of their hopes and fears, while still carrying the burden of the choice ourselves, so they know that part of our effort to keep them safe is ensuring that they will be listened to, but also that the ultimate responsibility of decision making is not something they have to carry. No matter the age of the child, though, these conversations always create the greatest sense of security possible when they begin with our careful and sincere listening.

We can also follow children’s lead. We can listen, not only to their fear, but also to their strong desire to show up for each other and protect each other. And we can try to locate the same courage to protect each other that we see in their walls of snow within ourselves. We can listen to the very lessons that we often try to convey to children about making a difference in the world—that even seemingly small gestures of care matter and these individual gestures add up when we work at them collectively. It’s natural to see the most obviously heroic acts and presume that, if we cannot take that level of risk, which we often can’t as parents whose personal safety has a direct bearing on our children’s safety, then we can’t do anything at all. But one of the very clear lessons of community, powerfully on display in Minnesota right now, is that so many different kinds of support are critical and impactful in weaving a net that meets an array of needs.

The frontline work of legal observers is essential. But so is contributing food to organizations that are delivering groceries to those who can’t leave their homes, or picking up groceries for neighbors ourselves. So is volunteering to do laundry or walking children to and from school or 3D printing whistles or standing outside a mosque or a school yard or caring for a neighbor's pets. It is the web of all of these gestures of care that really matters. And this is actually exactly what we often teach children. Nearly every lesson in community care that we impart to children involves the underlying idea that our individual small actions can add up to something bigger.

Children have very little power in the world, so understanding that they can still make a difference through their small, personal contributions, especially when those actions are part of a larger community of people making their own small contributions, is exactly how they learn to be engaged citizens and problem solvers in their earliest years. And we adults can take a lesson from the very curriculum of community that we so often try to impart to kids, especially when we, too, are feeling small, powerless, and overwhelmed—every little thing matters.

Children should not have to build walls of snow to protect their friends from federal agents. But, in doing so, they are telling us how clearly they understand the threat they are under and how important it is, for both the sake of real community safety and for each of our individual hearts, to make a practical contribution and to feel that our care and effort matters. For so many reasons, it’s important that we listen closely to children now, and that we both provide them with models of courage and care and learn from their own efforts to act on behalf of their friends.

Lastly, even in the worst moments, when it feels like there is nothing more we can say or do, when our own hearts are breaking open and we feel too exhausted and afraid to move forward, we can sit together and share in their witnessing. I’ve shared these words from one of my own mentors before, but they bear repeating here. As Jonathan Silin notes, even under the most difficult and frightening circumstances, when we feel we have nothing more concrete to offer children, we can sit beside them and acknowledge their experiences and our own.

"In the face of uncertainty, it is our willingness to approach the unimaginable and our commitment to bear witness that we can offer students of all ages. This is our most effective antidote to troubling histories and the difficult present. We cannot offer certainties nor can we promise to fix the world. But surely, surviving and bearing witness are reciprocal acts and we can say to our students, ‘Yes, this is how it is.’ And we can affirm: ‘Yes, we are here beside you. We can testify to your experience and to ours. Most importantly, we can teach you the skills and offer you the resources for telling your own stories...’"

Wishing you safety and the strength of heart to keep caring and showing up,

Alicia

P.S. I’ve included helpful & hopeful links below, as always. But, if you only click on two links today, I hope they will be this podcast with Autumn Brown and adrienne maree brown and this incredible compilation of practical resources for supporting Minnesota.

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

I have so many links open right now, it is hard to narrow them down. But here are a few that I think are especially worthy of elevating.

- Nonviolent Discipline Is Helping Turn the Tide on ICE

- "My Hands Were Really Shaky": High-School Journalist Documents ICE Raids

- How "Mamas of Cedar" Are Keeping Watch for ICE in Minneapolis

- An Emergency Dispatch with Autumn Brown & adrienne maree brown

- Stand with Minnesota - Resources for helping from near and far

- The People's Laundry MPLS - A simple way to help if you're in MN

- We Belong to Each Other - I've seen several videos of this being sung in the streets in Minnesota. The music is by Minnesota musician, Annie Rambeau, with lyrics from a poem by Nikita Gill.