Why Those Who Care for Children Make Easy Prey

Thinking about the past and present of child care hysteria

“All predators prefer a dinner that does not fight.

I won’t be swallowed limp and mute

into the python belly of the state.

Fighting together can feel like work well done

singing on the body’s trumpet.

Being eaten slowly is always a drag.”

~Marge Piercy

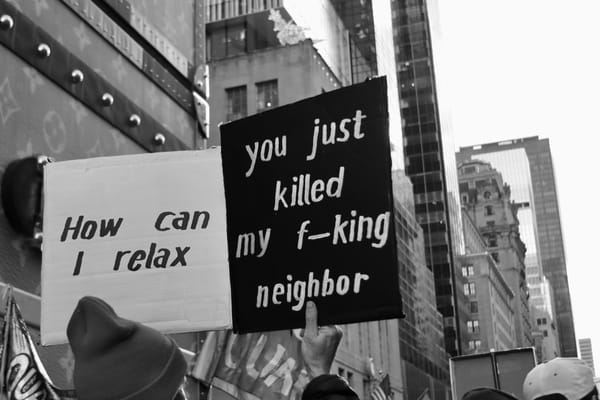

It is a strange thing to be part of a profession that is primarily made up of the most selfless, caring people you could ever know, and to see these same people villainized on a national level time and again. There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about the challenges of living through “unprecedented times,” but as the news about Minnesota day care fraud has spiraled over the past week, it’s all felt extremely and exasperatingly precedented.

A few points of clarity to start, because the facts in the majority of reporting have been very muddily conveyed: there is a kernel of truth in the fraud stories in that some child care centers have been under investigation in Minnesota, but the majority of the accusations are wildly lacking in evidence, and the cases identified by the state are already being handled by local officials. They are not breaking news. However, a viral video, made by a conservative influencer, has led to a frenzy of reporting and to the harassment of Somali day care staff, which is now proliferating across multiple states. The accusations stemming from the video are highly dubious at best and are creating a manufactured fever dream—and a sadly familiar one, stoking suspicion of those who do the largely under-compensated, often minimally respected, but profoundly essential work of caring for children. (This is an excellent primer on the situation, if you want to further understand the details.)

Child care workers are easy targets for many reasons. Early childhood education is largely composed of those demographics that hold the least social, political, and economic power. Most early childhood teachers are women and many are women of color, often immigrants. And they do work that is regarded with a level of hostility by those who think that mothers shouldn’t work at all and children ought to be cared for at home. Additionally, unlike teachers of older children, who are not exactly at the pinnacle of social respect in the U.S. themselves these days, most early childhood teachers are not protected by a union, and they are often not viewed as “real” teachers or "full" teachers, because they work with such young children. As the late early childhood champion, Maurice Sykes, said, following the pandemic,

“K-12 is seen as part of the public good whereas child care is seen as part of the service industry.”

Layer onto all of this the ease with which anything having to do with children, especially young children, understandably taps into our most primal protective instincts, and you have a perfect recipe for accusations, moral panic, and an instant source of blame for social fear and resentment.

When I first started teaching, the question of whether early childhood teachers should have any physical contact with young children was a common topic of professional conversation and administrative handwringing—not conversations, mind you, about what constituted appropriate or healthy contact, but rather whether any contact at all was too great a professional risk for teachers to take. I entered teaching nearly two decades after the cases that sparked what is now known as the “Satanic Panic,” which ripped through U.S. daycares, sewing fears of rampant child sexual abuse, including cultic Satanic rituals, in child care settings. Most of these accusations have long since been revealed as unfounded. But the deep anxiety that these scandals created was still palpable, and to some extent remains so today, both for parents afraid that their children are unsafe anywhere beyond their own supervision, and for teachers fearing the repercussions of the accusations that easily stem from these fears.

Some schools and day cares instituted policies that prohibited physical contact, including lap-sitting and hugs, which, after more than two decades in classrooms, I still have no idea how a teacher of two, three, or four-year-olds could possibly manage. Not only do young children need help with an array of physical tasks throughout the day, but they are also basically heat-seeking missiles when it comes to physical comfort and attention. In the course of a preschool day, if I had one child on my lap, I usually quickly had three children attempting to squeeze in next to each other. And every early childhood teacher, or parent of a young child, is surely familiar with the feeling of two small hands clasping your face and pivoting it toward their own, manually redirecting your adult attention from another child to the urgency of their own needs or ideas. Not only are young children in need of near-constant physical assistance and care, they are also still in the process of becoming fluent speakers, often relying on physical contact and expression to communicate. Depriving them of this contact is both a practical impossibility and detrimental to their developmental needs.

Many of these fears and some of the accompanying policies still linger today, decades after the actual cases fell apart. The most widely known case, at McMartin Preschool in California, which sparked many of the others that followed, turned out to have originated in the mind of a mother suffering from schizophrenic delusions. But fears, particularly parental fears, are difficult to quell. Understandably, our primary task as parents, on a deeply evolutionary level, is to protect our children from harm. So it makes sense that we would have difficulty setting aside anxiety for our children’s safety once it’s been stoked. As a result, self-protection has become a filter that is layered over nearly every aspect of early childhood teachers’ daily work, particularly when it comes to meeting children’s most basic needs. When I was a preschool director, it was not uncommon for teachers to ask for guidance on how to help a child who was not yet able to use the bathroom independently, or to ask me to come into their classroom to serve as a witness while they changed a diaper or helped to clean and care for a sick child.

I want to take a moment to pause here and acknowledge the fact that real child abuse does, of course, exist and is often treated with shockingly little belief or care by the very systems that are meant to protect children. This is because the most common perpetrators of actual abuse typically hold significantly more power, either over the child directly or in society more broadly, than preschool teachers usually do.

Family members are the most common perpetrators of child abuse. And, where systemic abuse does occur, it is most frequently in contexts in which significant power shields the perpetrators, such as the moral and institutional authority that long protected abuse in the Catholic Church, or—as we’ve seen vividly in the case of the Epstein files—when perpetrators are wealthy or politically powerful. Even within family contexts, existing power hierarchies tend to align with social and legal accountability. For example, fathers who are accused of child abuse gain custody 72% of the time, which is actually at a slightly higher rate than fathers who are not accused of abuse. Sexual abuse allegations, in particular, increase the likelihood of a father gaining custody to 81%. None of these statistics hold true for mothers, who of course can also be perpetrators of abuse, but who generally hold less social power and credibility.

Given the genuine importance of children’s safety, early childhood teachers are also among the most heavily screened professionals. They are fingerprinted and background checked, often through multiple systems at both city and state levels. They receive annual, required training in abuse prevention. And teachers are considered mandated reporters, which means they are obligated to report suspected abuse, not only in the home, but also among their own colleagues. All in all, there’s a strong argument to be made that young children are safer at preschool than in just about any other environment.

The current accusations, focused on Somali daycare providers in Minnesota—and now in other states, like Ohio and Washington—are very different from the abuse allegations of the 1980s and early 1990s. The current accusations are of financial abuse, not physical abuse. And it feels somehow symbolic that children are quite literally absent from the frame in these new stories, as internet content farmers show up on day care doorsteps with cameras in tow, expecting to be permitted to film other people’s children, only to use the apparent absence of children as evidence of their claims of fraud.

Having been the director of two early childhood programs, I feel confident saying that these child care providers are fulfilling both their ethical and legal obligations by keeping children away from these cameras. Most states mandate that day cares strictly control access (largely as a result of the very real security threat to children posed by the lack of gun regulation). The fact that children are missing from these videos is at once the point of the manufactured scandal, evidence of teachers actually doing the real work of protecting children, and representative of the fact that the children are very much beside the point in this particular outrage machine.

Rather than tapping into fears of abuse, the current scandal relies on a different, but also familiar and long-standing, social narrative. These most recent accusations, and the fervor they have whipped up, ring of the “welfare queen” myth, as Black women—this time Somali immigrants caring for other people’s children—are stigmatized and criminalized on the claim that they are taking advantage of government funds.

All of the day care centers featured in the viral videos have been determined to be operating normally by state officials. It’s also worth noting that the content creator who made and spread the video that now has millions of views has a history of anti-immigrant rhetoric and referred to Muslims as “demons” in the video—perhaps the most direct parallel to the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s and 1990s. Additionally, he was directed to investigate Somali-run daycares by the Minnesota GOP caucus, so the political motivation is not subtle. And, while there were some Somali immigrants charged in the original, state-run fraud investigation, the leader of that fraud case was not an immigrant; she was a white woman.

Despite all of this information, after over a week of reporting, a quick search of the news will likely still leave you with the impression that there is significant merit to the ongoing accusations. Headlines like, “Minnesota Investigates Child Care Centers Following Fraud Accusations” or “Everything We Know about Minnesota’s Massive Fraud Schemes” persist.

Meanwhile, federal child care funds have been frozen to all states, as a result of these accusations, pending review of administrative records, with little clear information offered to child care providers for how this review will proceed or for the likelihood of funds resuming.

If there is one starkly undeniable fact in all of this, it is that children, parents, and teachers will suffer, and those who will suffer most will surely be the children who were already at the greatest risk, due to existing inequities in child care access. As Maria Snider, the vice president of the Minnesota Child Care Association, said in an interview with NPR,

“It's going to mean people are going to lose their jobs—parents, early childhood teachers. Programs might be at risk of closing because of the crisis that's been in child care for decades. It's an underfunded industry, so something like this is just really like kicking us when we're down.”

When parents lose their jobs because they can’t access care, children are put in danger of every possible risk, from food and housing insecurity to learning loss. Many teachers are also parents, so this will hit them on multiple fronts. And, as we can learn from the earlier “Satanic Panic,” these moments of hysteria often have a very long tail, impacting children, families, and educators well after the initial sensational media frenzy has faded.

So, what to do?

When I was supervising student teachers, there was a little bureaucratic requirement that I’ve always found surprisingly moving and motivating. In the routine paperwork that instructors completed, in compliance with accreditation requirements, there was a question on the early childhood forms that asked if the teacher viewed themselves as “an advocate for children.” Interestingly, this question was not part of the form for teachers of older students. That little mandated question always struck a chord. It was a tiny bit of red tape that actually spoke meaningfully to the profound responsibility of early childhood teachers, not only to care for and educate the children in their own classrooms, but also to become a voice, more broadly, for the rights of the youngest children, who have the least capacity to use their own voices.

This is a quality, or rather a conviction, that nearly every early childhood teacher I’ve worked with, across a wide range of settings and pedagogies, has possessed—a fierce commitment to the welfare and wellbeing of children and a responsibility to stand between children and harm. It’s why the persistent vilification of these teachers is so heartbreaking. But it’s also where I find hope. And early childhood education demands hope.

My wish for this difficult moment is that others will join in this commitment. In this particular instance, that work will begin with developing a skeptical read on sensational headlines, and it will extend to making your own voice heard in defense of the services that support young children and the caring adults who provide those services.

Wishing you the security of the care you need and the strength of voice to demand it for others,

Alicia

More resources on today's note...

- Please call your representatives and demand that HHS child care funding be resumed in all states and that immigrant child care providers be protected.

- There is a lot of causal overlap between today's note and the note I wrote in the fall about children's rights. In case you missed it, here is that note from September.

A few things I found helpful and hopeful this week…

- On a brighter note, beavers saved a wetland restoration project and $1.2 million!

- This is very moving and makes me feel deeply hopeful.

- The Case for Hope: Transgender Rights Going Into 2026, by Erin Reed

- Lastly, Muppets! Not only did The Muppet Show define my own childhood, but my son watched old episodes of the original Muppet Show when he was very little, granting him a bizarre repertoire of 1970s and 1980s pop-culture knowledge for a kid born in the mid-2000's. So this makes me wildly excited during an otherwise terrible news week.